Living Too Close to the Ground

By Will Stephenson

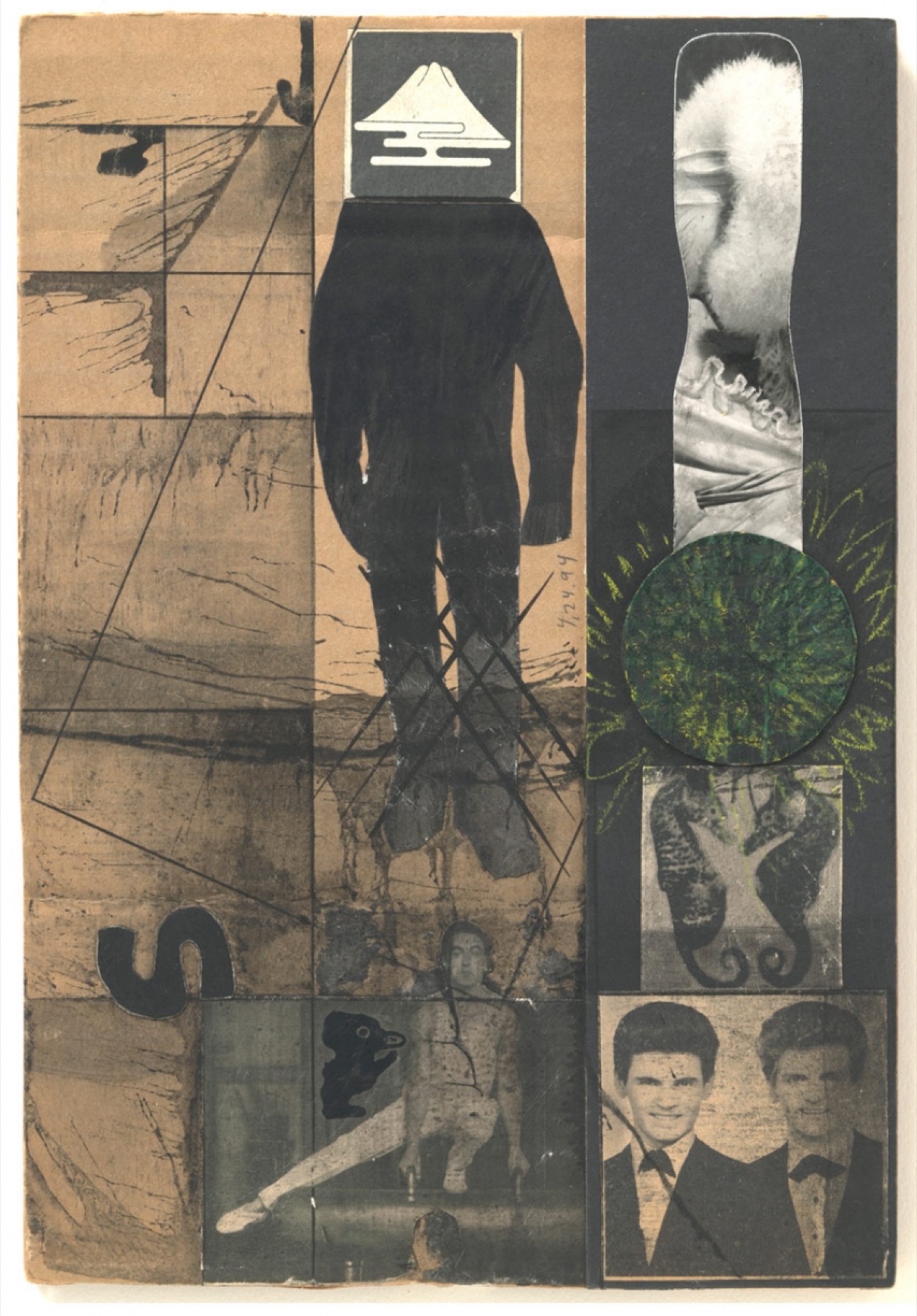

Untitled (Moticos with Every Bothers) (1953/1994) by Ray Johnson © The Ray Johnson Estate. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Sometime in the months before he dove off a bridge in Sag Harbor and drowned one night in January 1995, the artist Ray Johnson put the finishing touches on a collage he had begun nearly a half century before. Billed by the Museum of Modern Art as Untitled (Moticos with Everly Brothers) (1953/1994), the artwork was one of many that had trailed Johnson, unfinished, for the bulk of his career, assemblages of mixed materials and impulsive gestures, often made from cut-out images glued on cardboard shirt-boards—moticos was his own nonsense term for them. “I believe this piece was never shown before it was sold,” the curator of Johnson’s estate told me recently. The 1953 starting date makes it especially important, she said, rare in the Johnson timeline. He often claimed to have burned his early work.

Johnson, whom the New York Times once called “New York’s most famous unknown artist,” was an enigma in the art world of the 1950s and ’60s. His attraction to the glossier artifacts of pop culture made him an important precursor to Andy Warhol and the pop artists. Warhol was a constant reference point—a nemesis or protégé or friend—but Johnson never attained anything like his counterpart’s notoriety. “I’ve invented Flop Art,” he’d joke. “It comes after Pop Art.” He despised the art market and its rituals. Rather than “Happenings” he held “Nothings.” One of his oldest friends recalled that Johnson always appeared to be “planning his escapes from the dark interior of the house of the mind.”

I owe my own interest in Johnson almost entirely to the Everly Brothers. I came across his collage and found it gruesome and inexplicable and almost certainly the best commentary on the group I’d ever seen. Like their music, it’s filled with shadowy figures and incoherent qualities: a circle of green sandpaper, a yellowed photograph of a gymnast, images of twin seahorses, and, in the lower right-hand corner, just below the seahorses, a square publicity still of Don and Phil Everly, dressed in their standard tuxedos. Like their music, it has the sensibility of a dream.

There are no great books about the Everly Brothers. No classic documentary films. Despite their influence on American pop music, which would be difficult to overstate, or the great, gaping beauty and sadness of their music, we are left with no lasting monuments to their catalog beyond the catalog itself. That, and—along with other personal tributes—this sad, ugly, perfect collage by Ray Johnson, who finished the piece by scratching large Xs across its surface, some weeks before filing it away in a box, folding over a thousand dollars in cash into the pocket of his windbreaker, and diving off a bridge that January night. Critics still debate whether his death was a straightforward suicide or a “last performance.” As if it makes any difference.

“There seem to be two basic types of fans,” Consuelo Dodge writes in her deeply unauthorized (and out-of-print) fan biography of the Everlys, Ladies Love Outlaws. “There are ‘Donald people,’ and there are ‘Phillip people.’ I have seen a few who love both of them equally, but species such as these are rare.” Phil was a flawless singer with an admirable stage presence, but it’s Don I’m interested in. Don was the bleaker writer, the baritone voice, the left-leaning amphetamine addict with the darker hair and worse attitude. Phil watched him closely while they sang—neurotically, you think at first, until you realize it was just physically necessary. They had harmonized since near-infancy, but Phil still had to keep an eye on Don’s mouth to plot his precise harmonic course.

And though we’ve forgotten this, those voices marked the artistic vanguard of rock & roll from roughly the death of Buddy Holly to the Beatles’ debut on The Ed Sullivan Show. It was Don who showed Holly and his band how to dress, even recommending Holly try a thicker pair of black glasses. The Beatles, for that matter, wanted to be like the Everlys, too. “When John and I first started to write songs,” Paul McCartney has said, “I was Phil and he was Don.” They weren’t alone. “They were the best duet singers I ever heard,” Brian Wilson wrote. “I don’t even know how they did what they did.” Paul Simon called them “the most beautiful sounding duo I ever heard.” And who could argue with Bob Dylan, who said, “We owe these guys everything. They started it all”? (Is that enough of an endorsement?)

The thing about Don was that he rarely enjoyed any of it. “As a teenager, I had Hank Williams Syndrome. I created emotional havoc to make myself miserable, then I could write miserable songs,” he’s admitted before. And sure, the drinking and cheating and fame and prolific Ritalin use didn’t help—but by the 1960s and ’70s this was obviously no longer any kind of posturing. Don is the one who sang, “Will I ever have a chance again? Maybe then I wouldn’t lose, I’d win.” Don is the one who sang, “My heart can’t thrive on misery, my life it has no destiny.” Don is the one who sang, “Turn the wheel and let it spin, tip the glass and see the bottom, can’t you see you’ll never win?”

I have a brother. We’re about as close as the Everlys in age—under two years—which has always added to my fascination with the band. He’s the best friend I have, though we’ve shared too much life for that to come easily. Sometimes my brother speaks of being “out of sync,” and I think I know what he means—one of us has gotten distracted by life, we’ve fallen out of some kind of primal harmony. Like all brothers, Don and Phil were constantly falling in and out of sync. Most famously and lastingly, their partnership ruptured during a series of concerts at Knott’s Berry Farm’s John Wayne Theater in July of 1973. Don was drunk off tequila. “It’s over, I’ve quit,” he told a reporter. Midway through one set, he confirmed that the band was no more, saying, “The Everly Brothers died ten years ago.” By then, Phil had smashed his guitar and wandered off stage. They would try the occasional, doomed reunion in later years, but the bond was effectively severed. “It was one of the saddest days of my life,” Don told Rolling Stone.

In hindsight, I wonder how it could have come as a surprise. Don had experienced the sixties in a way that Phil hadn’t. He’d gotten stoned with Jimi Hendrix in the back of a limo; seen Joni Mitchell play the Bitter End; and dropped acid—“the best,” he’s clarified since, “Owsley’s Orange Sunshine”—but he was still trapped in his tuxedo. During the height of the Vietnam War, they played Saigon, at a benefit for an orphanage. “That night we sat on the roof of this house and watched them napalming stuff outside the city,” Don remembered in an interview. “That’s when it began to dawn on me that something was dreadfully wrong.” And as he later said of Phil, more simply, “We have different dreams and feelings.”

They’d tried going to Hollywood, like Elvis, signed up for acting lessons and shot screen tests in Technicolor. They even made a Western, in which they sang a song or two from their Top 40 repertoire and exchanged words like “Howdy, stranger.” It was never released and has been lost—burned, like Ray Johnson’s early work—but the story survives. Don was expected to deliver one of the film’s most crucial lines of dialogue, a process that took innumerable reshoots. He couldn’t remember the phrase, it was so vapid, or so confusing, or both. By the eleventh take, the crew wrote it on a table for him: And bravely dare the danger that nature shrinks from.

Sometime around 1978, both Ray Johnson and Don Everly decided to become functional recluses. Johnson had left Manhattan after he was mugged at knifepoint on the same day, by some cosmic coincidence, that Andy Warhol was shot. He moved out to Long Island, and hardly anyone was ever allowed into his home after that. By the end of the decade, the curator of his estate said, “he ceased to exhibit or sell his work commercially.” Don made a similar calculation. As he explained to Billboard in 1980, he’d quit recording and touring after the failure of his seventies solo albums, the death of his father, and the fact that, “Music suddenly wasn’t fun any longer.”

Decades later, Don finally achieved his longtime dream of returning home to Kentucky. He purchased a rustic hotel in the region where generations of his family had once put down roots. “The town where I was born doesn’t exist anymore,” he told a journalist from Life as he showed him around, driving up Route 431 in Muhlenberg County. “When the coal was all gone, they tore the town down.” His father, Ike, had been a coal miner, like his father before him. Part of the reason Ike got into music and radio in the first place was so his sons wouldn’t have to work in the mines, and they never did. But when Phil, a smoker, died of lung cancer in 2014, Don couldn’t help pointing out, morbidly, that it wasn’t so different from Ike dying of the black lung. Don said nice things about his brother, too, and you could tell he meant them, though they had never entirely resolved their problems—not every problem has a solution. And anyway, as Don put it in a press release, “I always thought I’d be the one to go first.”

“He had a feeling of an interior emptiness,” a critic and friend of Ray Johnson’s, William Wilson, wrote of him. “The emptiness was experienced as a kind of Nothing, or Void, and Ray found many angles from which to point to various nothings and various voids. A dream had the correct evanescence for him, as for a moment it was everything in consciousness, yet later was almost nothing.” This may be the most powerful resonance that Johnson located in the music of the Everlys, the reason he spent all those decades reworking his collage. Don’s best songs were always about dreams, about “various nothings and various voids.” I think of his solo version of the Louvin Brothers’ “When I Stop Dreaming” as the height of a certain strain of drug-addled, soul-searching, country fragility. “Where is that dream of me that used to seem so wonderful and real?” he asked on another solo track. One of the Everlys’ biggest hits, while they were still teenagers, was “All I Have to Do Is Dream”—that’s the one they’re best remembered for. “Only trouble is,” they sang, “I’m dreamin’ my life away.”

I wonder if Don is aware of Ray Johnson’s collage, but I have to assume he isn’t. “I am very interested in how music connects with the art world,” he said once. “The artists are aware of the music, but the music’s not aware of the artists.” Today, he lives in Nashville, where he moved after his hotel in Kentucky burned to the ground a few years before Phil died—a “total loss,” according to the fire department. So much for going home.

“Love is Strange” by the Everly Brothers (live in 1970) is included on the Kentucky Music Issue CD.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.