Young, Foolish, Happy

By Jill McCorkle

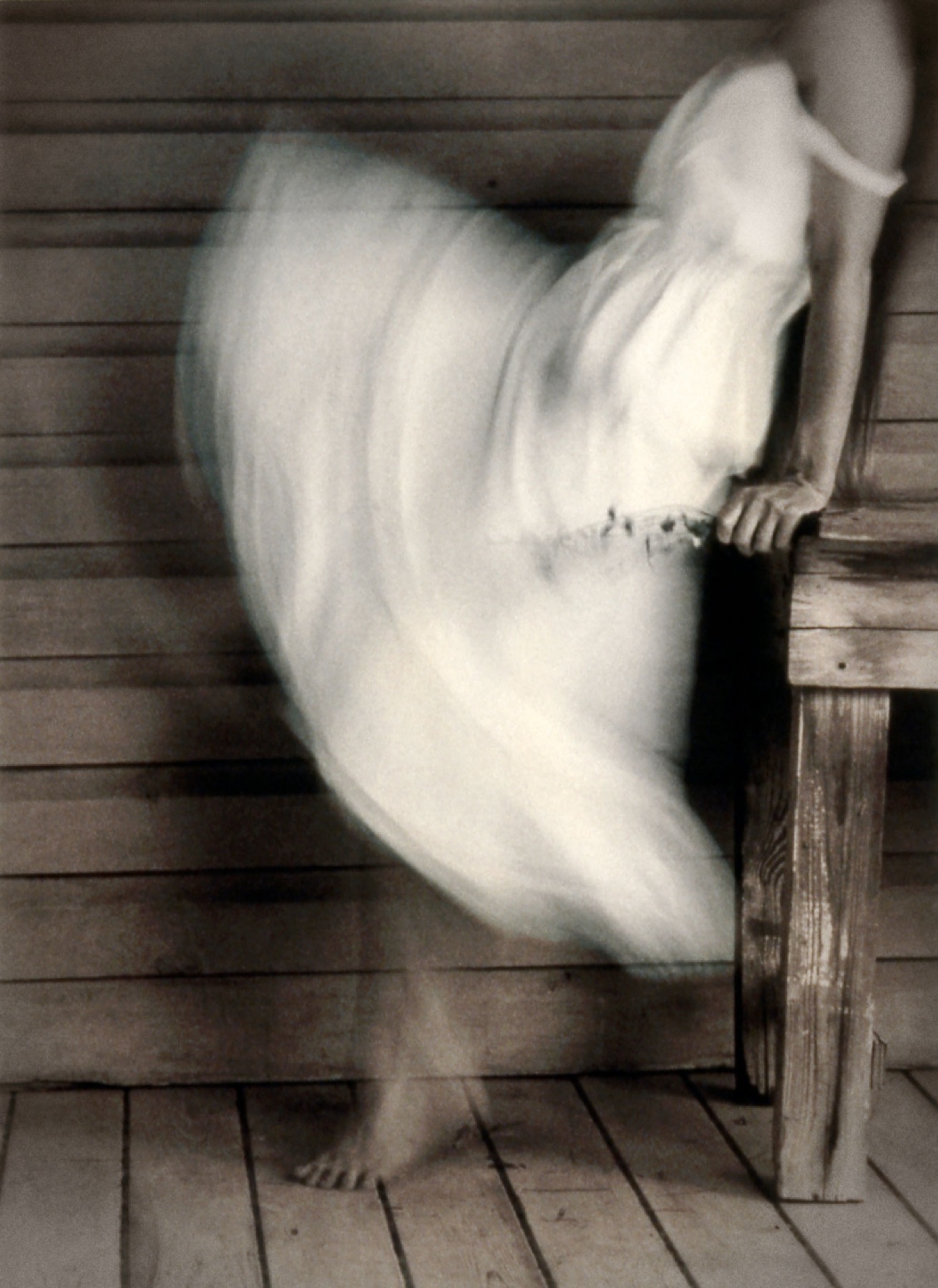

“Judi’s Dance” by Marthanna Yater | marthannayaterphotography.com; Instagram: @marthannayater; Twitter: @marthannayaterp

Growing up in eastern North Carolina in the sixties and seventies, I was always aware of what people referred to as beach music—originally a branch of r&b that grew to overlap with both rock and soul. In fact, when I have wanted to pull up all the oldies I grew up hearing—the music I think of as soon as spring comes to the Carolinas—Pandora has taken me to Frankie Valli or the Beach Boys (some summery sounds but very different) or Motown artists like Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, and the Temptations (other faves and getting much closer, but still not the same, despite some overlap in songs and artists). Finally, I put on the Tams, a band from Atlanta, Georgia, and one of my favorites, to hear a medley of their hits from “I’ve Been Hurt” and “You Lied to Your Daddy” to their popular anthem offering sage advice, “Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy,” and on into hits from other old familiars. That takes me right where I want to be.

My hometown is just over an hour from Myrtle Beach, and so it was not unusual for people to make the pilgrimage to the Pad or the Spanish Galleon or Fat Harold’s on Ocean Drive to hear bands like the Embers, the Tams, Chairmen of the Board. I had heard the songs and the names of all the bands long before I was old enough to go. I have a vivid memory of a teenager in the neighborhood, her hair rolled on jumbo orange-juice cans while she danced around barefooted in pedal pushers and a cropped eyelet top, playing Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs’ “May I” over and over again. “May I” was a bouncing, flirty track, filled with doobie-doos and oohs—and then that falsetto inquiry: “May I have your love? / May I be your boy-o-oy?” The successive lines go “May I speak with you? / May I bring you joy?,” but for the longest time I was convinced of a more scandalous misreading, one that swapped speak for sleep—a thought that would be secured a year later, when the girl with the juice cans in her hair got married right out of high school, then promptly had a baby.

I would have been seven in 1965 and what I remember is the girl’s mother saying that she had played that 45 about a hundred times since she bought it. I bought my first 45 not long after—Willie Tee’s “Walking Up a One Way Street” (b/w “Teasin’ You”). It was summertime music, what blared out of the speakers at the local pool where we went to swim or the transistor radios parked beside those stretched out on beach towels, bodies greased up with baby oil and iodine. Bikinis were just finding their way to Lumberton, North Carolina, and my cousin visiting from Phoenix shocked the pool patrons in her Hawaiian-print number, which made my older sister and me feel both proud and popular by association.

The Drifters, the Platters, the Impressions, Jerry Butler, the Catalinas, the Fantastic Shakers, Band of Oz, the Tymes, and the Showmen—along with the artists already named—make up the backbone of this branch of music and the dance that grew out of it: the Shag. Not to be confused with the British meaning, in the Carolinas the Shag is a loose-limbed kind of shuffle, complete with turns and dips and slides.

By the time I was an undergraduate at UNC Chapel Hill in the late seventies, beach music was still popular among bands visiting campus, and we spent hours working on our dance moves in the dorm. I was lucky that I had a roommate who was adept enough to lead, and so she was in high demand as we practiced the slides and pretzels and turns. If you didn’t have a partner, you could tie something like your bathrobe sash or a belt to a doorknob and practice that way, shuffling and turning and singing along. And of course we had our favorite songs. We loved the Catalinas’ “Summertime’s Calling Me” and played it as frequently and as loudly as my neighbor had played “May I” a dozen years before. We also liked the Tymes’ “Ms. Grace” and the Globetrotters’ “Rainy Day Bells,” Billy Ward & the Dominoes’ “Sixty Minute Man” and “I Told You So” by Janice. And it would be hard to talk about beach music without a nod to General Norman Johnson of both the Showmen and Chairmen of the Board, who wrote “39-21-40 Shape” and “It Will Stand”; I’ve always been amused by the biblical overtones in both. “You could make a blind man see / You could make a cripple man walk,” Johnson sings. In “It Will Stand,” he tells those of us not on board with rock & roll: forgive them for they know not what they’re doing. Perhaps he was reaching out to his gospel roots and his earliest singing career as a six-year-old in his church choir, or maybe he was just acknowledging a branch of music that rose to power with a slew of followers ready to witness and sing and dance.

Beach music is something I never tire of. It’s its own subgenre, a body of great doo-wop and r&b artists, and it conjures summer and the ocean and a kind of laidback freedom; many of the songs invite you to sit back, drink a beer, soak up the sun, dance. They invite you to be young, foolish, happy.

“One More Time” by Salty Miller is a North Carolina Music Issue bonus track.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.