Etta Baker’s family photo (ca. 1960s). Courtesy of Edgar H. Baker

That Chord!

By Rebecca Bengal

Growing up, Etta Baker was among many secrets I didn’t know about the place where I lived: Morganton, North Carolina, at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a town of textile mills and state institutions, furniture factories and a chicken processing plant, pop. 16,000. I didn’t know that Morganton was home, a thousand years ago, to the native village of Joara, and Fort San Juan, the first European settlement in the United States. I didn’t know that there were communities in our midst named Worry and Joy, or that Jules Verne set a 1904 novel here, casting Table Rock Mountain as the “Great Eyrie.” I didn’t know of the underground juke joints—the Tombstone, the Sundown, the Jam Boogie—or that local Johnny Bristol became a Motown producer and counted his funk ballad “Morganton” among his recordings. Most regrettably, I didn’t know Etta, who lived here most of her life and was one of the foremost players of the Piedmont blues, mentioned in the same breath as Elizabeth Cotten and Blind Boy Fuller.

Until her death in 2006 at ninety-three, Etta remained one of the last living links to the sound of a long-gone world. “What you are hearing is direct from the 1800s with very little mediation,” David Holt, host of the PBS show Folkways, who played with her frequently in her later years, put it to me. “Nobody, nowhere plays like she did,” Taj Mahal told me recently. Legend goes that after hearing Etta’s first recording, a young Bob Dylan traveled to Morganton, knocking on her door. For nearly half my life, I lived a mile from Etta’s house. I must have passed that door dozens of times without ever hearing the music that existed behind it.

Now when I visit, I walk to the city auditorium where under a tree rests a bronze sculpture of a woman, tall and striking, slim fingers picking the guitar in her hands, an expression like joy carved in her face. Unveiled in 2017, a year of toppled monuments, it is a rarity: a statue of a woman, an artist, who was African American, Native American, and Irish American—and proud of them all. After emancipating herself from twenty-six years of factory work, Etta became a professional musician in her sixties, accepting an NEA award alongside B. B. King, performing with Doc Watson, recording with Taj Mahal, and opening for Ray Charles.

I didn’t become aware of Etta until the early 2000s, when I was living in Texas. In 1991, when Etta released her first solo album, One-Dime Blues, at age seventy-eight, I was too myopic to notice. I was obsessed with the Velvet Underground. I attended a high school with the taunting name of Freedom. I’d absorbed the idea that one can not only be defined by place, but can be confined by it. I didn’t want to hear anything that reminded me of where I was raised, for fear it might hold me there forever.

“You wanted blue hair!” Taj Mahal said, when I confessed this.

“I did!” I said. “But I’ve been circling back to this music—”

He stopped me. “And now all those people are gone.”

On a winter night in Brooklyn I lowered a turntable needle onto Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians, listened to Etta Baker’s “Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad” and “One Dime Blues,” then flipped to the other side. Within the first notes, my eyes inexplicably flooded. There is little in “Railroad Bill,” an early twentieth-century blues ballad of a “mighty mean man,” a turpentine worker, a train-robbing killer with supernatural powers, to trigger tears. But Etta renders “Railroad Bill” wordless, like most of her music. Her fretting takes on a near-vocal quality. The current of the song is a mysterious and bottomless minor chord that felt viscerally familiar, unhinged in time. I cracked a window, let it spool outside. I played it again, seized by a desire to understand who and where this fundamental sound had come from. Over the next months, I’d go back to Etta’s town—my town—to try to find it.

Etta Baker rose before the sun to play guitar, an hour every morning. She was warm and funny. She cultivated the orange daylilies that now grow at her statue’s feet; she “dearly loved” to drive fast; she foraged for medicinal roots in the woods along the twisting trail of the Johns River where she grew up. Born Etta Lucille Reid in 1913 in Caldwell County, roughly twenty miles from Morganton, Etta was the youngest of eight in a family through which music traveled like blood. Sally, her mother, sang and played Jew’s harp; her father, Boone, guitar, clawhammer banjo, and harmonica—“mountain songs,” Etta said; all the children played, too. When Etta was three, Boone sat her on the bed, put a guitar on her lap, and taught her the way his father taught him: using just thumb and finger, a style she’d refine for the rest of her life. “He wasn’t as smooth as she was, seems to me,” Etta’s son Edgar, the only of Etta’s nine children who still lives in Morganton, told me recently. “I don’t know nobody as smooth as she was. She could play the stew out of a guitar.”

The Reids were farmworkers, pulling ten-hour days in the fields. When Etta was three, they moved to Chase City, Virginia, to work tobacco. The blues showed up on their doorstep. “A bunch of people was serenading us for being newcomers,” Etta said to the writer Emily Herring Wilson in a 1983 interview. Neighbors marched around the house playing until Boone, “thrilled to death,” invited them in. “One of the men in the group taught Daddy this ‘Carolina [B]reakdown,’ and then he set down and taught it to me.” The song became one of her signatures and the title of a 2006 duet album featuring Etta and her sister Cora Phillips.

When the Reids moved back to Johns River, they brought this blues to the hills, mixing it with the jigs and reels they played at fish fries, dances, and other “entertainments.” Neighbors brought washboards; sometimes Boone would buckdance. “I remember when the only way to get from one house to another was these little narrow passes and one family would walk to the other one and they would be playing their music as they would go along,” Etta said in a television segment filmed on Cora’s porch in 1989. “The whole mountains was ringing with Carolina blues.”

The Carolina blues, or the Piedmont blues, is generally quicker, livelier than the Mississippi Delta blues, with syncopated, stripped-down picking patterns repeated over changing chords: a rural, ragtime blues for dancing. In his 1977 history Sweet as the Showers of Rain, the blues scholar Samuel Charters traced its path across land that “heaves into lines of stony ridge, then into the raw wilderness of the Appalachian Mountains, dark and wood-covered in a sweeping mass . . . ” It is an older blues than the Delta, Charters theorized, because slaves were brought to the Carolinas and Virginias earlier, and the West African Mandingo people carried the memory of the kora, a stringed instrument made from dried calabash. In those stony ridges the technique of playing kora translated to the banjo, then the guitar: a “rather free finger picking with a rhythmic center in the alternate thumb stroke.”

“Everyone wants to ornament a piece, but she had this restraint,” David Holt said. “She left room in the songs. It’s just a simple riff, over and over, a loping blues.” “I call it travelin’ music,” Edgar said when I visited him and his wife, Stephanie, in Morganton. “There’s a motion in it.” When Etta wanted a slide, like her father, she sometimes reached for a bottleneck. “Mrs. Baker uses no finger picks in playing the guitar and in ‘John Henry’ tunes it to an open chord and plays with a jackknife blade,” read the liner notes that accompany Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians, recorded in 1956 when Etta was forty-three. Edgar showed me this technique by using his elbow as the guitar, flicking open a pocketknife, and placing it between his ring finger and pinkie. “The tone of the music, it sounded different,” he said. “It sounded like back in the hills.”

“Before I met Edgar’s mom, I didn’t even know a woman could play guitar like that,” Stephanie said. “I didn’t even realize a woman could play guitar! I grew up out here in the country, and back then it was all men.” Stephanie said it gi-tar the way Edgar had, the way Etta herself did, lilting over the syllables, making a music of the word itself. The family’s accent is soothing, lyrical, and clarifying, as when Edgar told me his mother was a “poem writer,” too.

Edgar was a baby in 1946 when Etta and his father, Lee Baker, a piano player and singer she had married ten years before, moved the family from a cabin in Johns River to a house in Morganton. Lee got a job at a furniture factory; Etta at a Buster Brown mill (they made the baby clothes, Edgar told me, not the shoes). She planted cherry and plum and apple trees in the garden, and they added four more children to the family—nine in all, including two sets of twins.

I told Edgar I’d heard one reason Etta didn’t professionally pursue music in those years was that Lee, though himself a musician, was against it. Edgar recalls differently. “When she played, he sang along,” he said. “He knew all the words. I don’t remember him telling her not to. My daddy was a talker. He’d make a point of letting people know who she was and how she could play. Daddy would take us all over the mountains. We could’ve just been out riding and ended up at Cone Mansion on the parkway and Daddy might’ve started talking to whoever owned the place and next thing you know, Mother’s on stage.”

Much like Mike Seeger chancing to witness the housekeeper Elizabeth Cotten idly flip over a guitar and play the blues of her childhood, a coincidence brought Etta and one of the great folklorists of the twentieth century together one summer afternoon in 1956, on the porch of a mansion museum on the Blue Ridge Parkway. On one hand, it’s stunning to imagine that without this alignment of events, much of the world might never have heard Etta Baker’s music. But Etta would have gone right on playing regardless.

Paul Clayton was already a song collector and folksinger when he arrived in Greenwich Village in the 1950s—“elegiac, very princely—part Yankee gentleman and part Southern rakish dandy,” Bob Dylan, who met him in 1961, writes in Chronicles: Volume One. Clayton kept a cabin in Virginia, too; he’d drive over creek bottoms in the antique Fords and Chevrolets he favored and lug his tape recorder and dulcimer across swinging bridges. Clayton was gay, and Tim Duffy, executive director of Music Maker Relief Foundation, who after Clayton’s death tried to track down the master tapes of Etta, marveled to me at Clayton’s apparent ability to talk himself into these “tough living rooms” in the hills.

In 1956, Clayton brought Irish folksinger Liam Clancy and Guggenheim heiress and Tradition Records founder Diane Hamilton to Virginia and North Carolina. Bearing Shure microphones and an Ampex recorder, they came seeking “time capsules of medieval culture” hidden in the “dark hollows,” Clancy writes in his memoir. But they went sightseeing, too, and, in some versions of the story, at Cone Mansion they met Etta Baker and her family, and she was playing her guitar. Clayton, transfixed, arranged to record Etta and her father in Morganton the next day for his compilation: field recordings of Virginia and North Carolina players on guitar, banjo, dulcimer, and harmonica.

In Etta’s living room Clancy watched those early sessions; later he recalled how this “incredible music flowed from this young housewife while she kept complete control over her whole family just with her eyes. . . . When she glared at the kids, they daren’t breathe.” In five songs, including clean, startling renditions of “One Dime Blues” and “Railroad Bill,” Etta “eclipsed” the record, Clayton’s biographer Bob Coltman wrote.

Sixty-two years later, Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians remains in print. “It was one of the most widely dispersed records of this music,” Wayne Martin, executive director of the North Carolina Arts Council and a collaborator of Etta’s, told me. The album moved through the Village folk scene, into college towns where Elizabeth Cotten, Sleepy John Estes, Roosevelt Sykes, and Mississippi John Hurt played coffeehouses. Taj Mahal first heard Instrumental Music in the early sixties. “Here’s this cover drawing of an Appalachian dude with his floppy hat on and cabins in the hills, and then I hear ‘Mrs. Etta Baker’ playing and I’m just flat out,” he said. “That chord! That chord! That chord! The first time I heard it I had to know who made it. It’s like a chord that doesn’t exist. It’s a brokenhearted chord. It’s like a haunting, melancholy, brokenhearted chord.”

Growing up, Taj encountered a music that sounded like it was “disappearing.” “It was black music, but it was also country music. It turned out to be this fingerpicking that gave me a feeling of being connected to an older style of music that I assumed was African, though I didn’t know.” I said that might be the truest definition of the Piedmont blues I’d ever heard. “It was that little . . . somethin’-somethin’,” Taj said. “I didn’t have no ‘ethnomusicological’ term for it. My name for it was stumblepicking.” Stumblepicking? “Meaning,” he said, “you’re kinda stumbling over the notes to make them. That chord of Etta Baker’s on ‘Railroad Bill,’ it was like an E7 going into an F but it doesn’t stay there. It moves. It jars you. I found something close to it by accident once, and I could probably spend my whole life trying to find it again.”

That chord! It allegedly inspired Bob Dylan, who during his first year in New York recorded “Railroad Bill.” “We hoped to visit Etta Baker, the great blues guitarist famous for her song ‘Railroad Bill,’ but it never happened,” Suze Rotolo, Dylan’s girlfriend in those days, arm-in-arm with him on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, wrote in a memoir. They made it at least as far as Clayton’s cabin near Charlottesville. “To impress the folkies back in New York, Bob joked, we should say we met her anyway, but we never did. You could blow your cool by not being cool about things like that.”

Instrumental Music had little immediate effect on Etta’s life. “People in Morganton didn’t appreciate her in those early years,” John Fleming, director-in-residence of the National Museum of African American Music in Nashville, told me. She reportedly turned down offers to play the Newport Folk Festival; had she accepted, she might have become as famous then as Elizabeth Cotten, who did take the Newport stage. Grievous hardships intervened. In the winter of 1967, within two weeks, Etta buried both her son David, killed in Vietnam at the age of twenty-one, and her husband, Lee, paralyzed by a stroke three years earlier. Eight years passed before the next song collector came calling.

In June, I found a copy of Music from the Hills of Caldwell County, long out of print, and called Delta X, née Stephan Michelson, in Hendersonville. In 1975, a statistics professor on leave from Harvard, Michelson converted a mail truck into a camper and headed to Caldwell County looking for the prodigiously talented family of musicians he’d heard about. The South, he said, was full of “terrific people.” When he camped in a meadow, a family knocked on his window: if he heard gunshots, not to worry, they were just hunting frogs. When he parked the truck in the yard of Etta’s sister Cora, he was welcomed. Over two weeks, Michelson recorded Cora and her husband, Theopolis “The” Phillips, and Fred and Babe Reid, and Etta, who drove out from Morganton.

Michelson recalled, “I found Cora and Etta to be very stiff people.” I was surprised and said so; in talking to nearly a dozen people who knew Etta well, I’d heard the opposite. But he repeated: “She wasn’t a flexible musician.” This was also at odds with what others said; I wondered aloud whether, in Cora’s house near the old family home, Etta had slipped into the role of a little sister, rather than of an artist.

Michelson considered. “You know, I was selfish, too, in a way,” he said. “I would take what I could quickly. I was living this weird life in which nothing connects. And I felt like a lot of people I knew got trapped in their lives.” Michelson’s liner notes in Caldwell County nonetheless hint at a greater future for Etta: “The only performer on this record who lives on a paved road or has running water in her home; and she is the only one to play an electric instrument. She is hoping to join a rock band and travel when she retires from the mill.”

Etta never joined a rock band but around 1976, she gave her notice. “There was a man came down from Portland, Oregon, and he said, ‘You oughta pick up your guitar and quit work,’” she told an interviewer. “Well I thought about that—it was on a Wednesday, and Friday I quit. Went to the office and told them I was quitting. And I did. And I’ve enjoyed every day since.” She performed throughout North Carolina, eventually internationally. She wrote new songs, too. “I dream a lot of my chords,” she told David Holt.

“You get them in your head?” he asked.

But Etta, who’d played a concert with Cora in Tennessee during the 1982 World’s Fair, meant it. She had a dream she’d call “Knoxville Rag.” “It was like putting a crossword puzzle together. This was like a quarter to three and I slid my sister’s guitar out from under her bed and I went out on the porch and I put my dream together.”

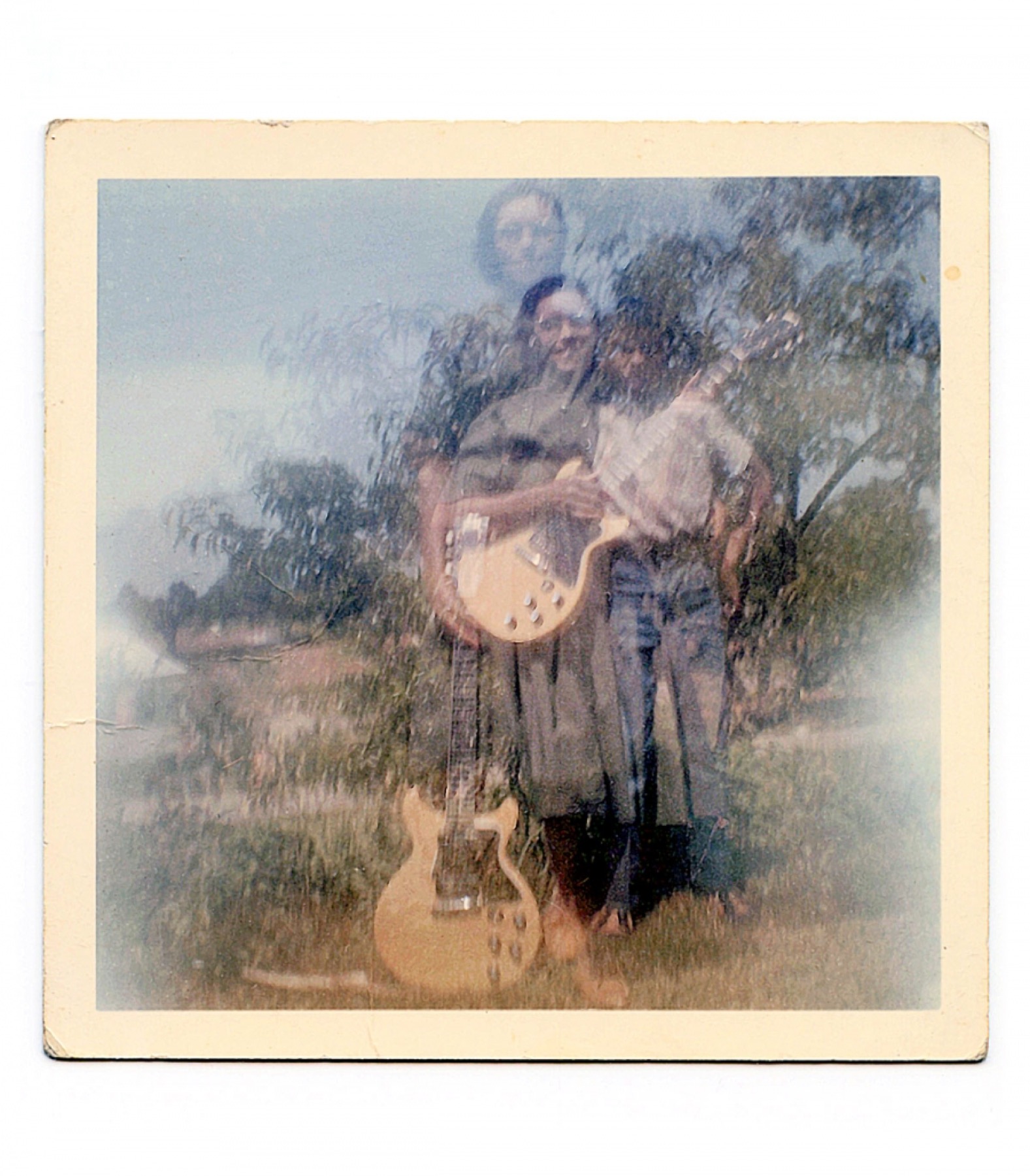

Etta’s house remains much as it was when she lived there—trees flowering in the yard, spices in the rack, a stuffed purple elephant on a hibiscus-print bedspread. (Her Stratocaster, her Takamine guitar, and other artifacts are displayed inside the city auditorium.) Home for a visit, I sat in Etta’s guitar chair on the porch, and Edgar and Stephanie and I looked through pictures of Etta in the seventies, on the cusp of her second life: double-exposed, holding her guitar; playing music in the garden; stylish in flared jeans and pointy boots, posing across the hood of a car; Etta’s instruments piled on a bed.

When Etta went pro, her admirers were overwhelmingly white—people who knew her from the folk days. She played Merlefest, won a North Carolina Folk Heritage Award. “At first I was like, where are the black people?” Stephanie said. “And then they started to come out, too.” On the strength of One-Dime Blues, and, later, her alliance with Music Maker, Etta was recontextualized as a blues musician.

“At first people were like, ‘Oh, but I already know Libba Cotten,’” Tim Duffy told me. As if, I asked, they’d found one African- American woman Piedmont blues guitarist and couldn’t possibly make room in their heads for another? “That’s it,” Duffy said. “Part of my working with her was to show people how good she was and how unique.”

“They roll differently, Elizabeth and Etta,” said Taj Mahal, who toured frequently with Elizabeth Cotten. “Etta could really play blues, different rags.” In 2004, he recorded an album with Etta on her porch. “I’m playing in deference to her,” he said. “She’d play a little bit and then she’d look over and say, ‘Now what have you got?’” On that record and others, Etta subtly reworked her repertoire. Two distinct versions of a song might appear on the same album—to the end of her life, Etta remained rooted in the spirit of music in the oral tradition.

When at last it became troublesome to pick the guitar, Etta returned to her father’s instrument, playing to the memory of those ephemeral Johns River nights. “She’d say, ‘My goal is to evoke what I remember hearing [Boone] play and his father before him,’” Wayne Martin told me. “‘He could make a banjo smoke.’”

“Railroad Bill,” however, remained her own, on either instrument. “I expressly asked her, did he play that chord? And she said, ‘No, I put that chord in there myself,’” Martin said. He had his own name for it: “the ‘suspended chord.’”

I thought about what Stephan Michelson said. Of all Etta’s recordings, Caldwell County is the only one that doesn’t include a version of “Railroad Bill.” Maybe the perceived stiffness was a meeting of two divergent viewpoints: Michelson, looking to riff, about to quit academia, and Etta Baker, who for decades, even as she authored her own chords, dedicated herself to preserving an endangered music. None of her children continued to play the old music. “It makes me some lonesome, hearing that chord,” Edgar, whose bass playing has been paused by arthritis, told me. She must have realized she was a conduit, a bridge between the nineteenth and eventually the twenty-first centuries.

I wanted to connect that ancient, disappearing music with places I thought Etta might have traveled. The family homes are gone, Edgar said, but a fine summer rain fell on the Johns River as I drove the dirt road running alongside it. I crossed Reids Creek, then Sally Creek. “Might be, might be,” Edgar had replied when I asked if they were named for Etta’s parents. The graves of Madison B. Reid and Sally S. Reid, born in the 1870s, are marked by two aged slabs on a hilltop in nearby Dulatown Cemetery.

Driving back to Morganton, I found a sign: the crossroads of Worry, weeds grown over the ry. Had Etta been here, too? “If you’ve made it to Worry, you’d better go to Joy!” a feed store proprietor advised. I slid Carolina Breakdown into the stereo and went searching. Though I’d never heard this music when I lived in Morganton, it must’ve lodged in my mind subconsciously, sound waves from Etta’s porch mapping themselves onto our shared town. I thought about how “Railroad Bill” had shocked me into tears. That chord! There’s an aching in it, a break, a tussle between the twin polarities of these pointedly named places. That some-lonesome suspended heartbroken haunting lost ancient chord . . . the name for that sound, I realized, is home.

“John Henry” by Etta Baker feat. Taj Mahal is included on the North Carolina Music Issue Sampler.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.