How Data Center Alley Is Changing Northern Virginia

When data gets heavy in Loudoun County

By Mac Carey

Courtesy of Piedmont Environmental Council, Hugh Kenny

Loudoun County—situated like a right-side feather on the northern cap of Virginia—is referred to as “Data Center Alley” because it carries more than seventy percent of global web traffic via over 200 data centers. Google, Meta, and Amazon have all staked claims here, with dozens more on the way in one of the most affluent counties in the United States. Over the course of my childhood in Loudoun, the economic reach of D.C. government contracts expanded every year, and dairy farms were replaced by data centers and Tyvek-wrapped walls of new developments climbed farther and farther down the banks of the Potomac River.

Data centers are warehouses of internet servers, wires, and data drives. These sprawling, humming bunkers have become essential infrastructure in the twenty-first century. Their round-the-clock operation is what allows us to order off Amazon, place a bet on FanDuel, or stream a show. Data center demand accelerated during the pandemic, then shifted into warp speed by AI. “Data centers are kind of critically interwoven in our lives today,” admits Gem Bingol, senior land use field representative for the Piedmont Environmental Council, an environmental nonprofit and land trust for the region.

The industry brought not just jobs, money, and tax revenue, but additional collateral impacts. The transmission of all this information requires an immense amount of electricity, burdening the county’s power grid and water resources. An individual facility can consume ten to fifty times the amount of electricity as a standard office building, fifty-thousand times the amount as an average home. Data centers and data transmission networks have a greater carbon footprint than the airline industry, and according to the International Energy Agency, account for more than one percent of total greenhouse gas emissions nationally.

“Whoever controls the energy affects the community,” says Chris Miller, president of the Piedmont Environmental Council. “And that’s a big problem of what Loudoun did over the last five years. They said yes to the land use without looking at the effects of the energy demands.”

Courtesy of Piedmont Environmental Council, Hugh Kenny

For ten years, Loudoun has been the fastest growing county in Virginia, adding just under 100,000 people to its rosters since 2014. My attendance at the county’s schools since kindergarten was such an achievement I was featured in my high school yearbook for it.

The evolution from bucolic backwater to diverse exurb hasn’t been seamless. Loudoun may be the linchpin shifting the state to safely blue in presidential elections since 2008, but it wasn’t until 2020 that the county courthouse’s Confederate statue was removed (after being spray painted with obscenities).

Into the mid-1990s, my high school was derisively called “Cornfield High” by rival schools. Now my hometown, Ashburn, is referred to as “Cashburn.” Loudoun County has the highest median household income in America, at $147,111. Much of that can be attributed to technology jobs.

Drawn by tax incentives, fiber optic infrastructure, and a ready supply of educated workers, the data center industry began moving here in the 1990s. Today, data center capacity in northern Virginia is greater than that of Dublin, London, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Singapore, and Sydney combined. Northern Virginia’s colocation data centers, centers that serve a variety of smaller companies, grew nearly five hundred percent between 2015 and 2023. Growth in Silicon Valley was less than half that.

At a January 2024 meeting of concerned residents at a local high school on the edges of western Loudoun, a Piedmont Environmental Council representative announced from the auditorium stage, “The data center industry is the old adage of too much of a good thing.”

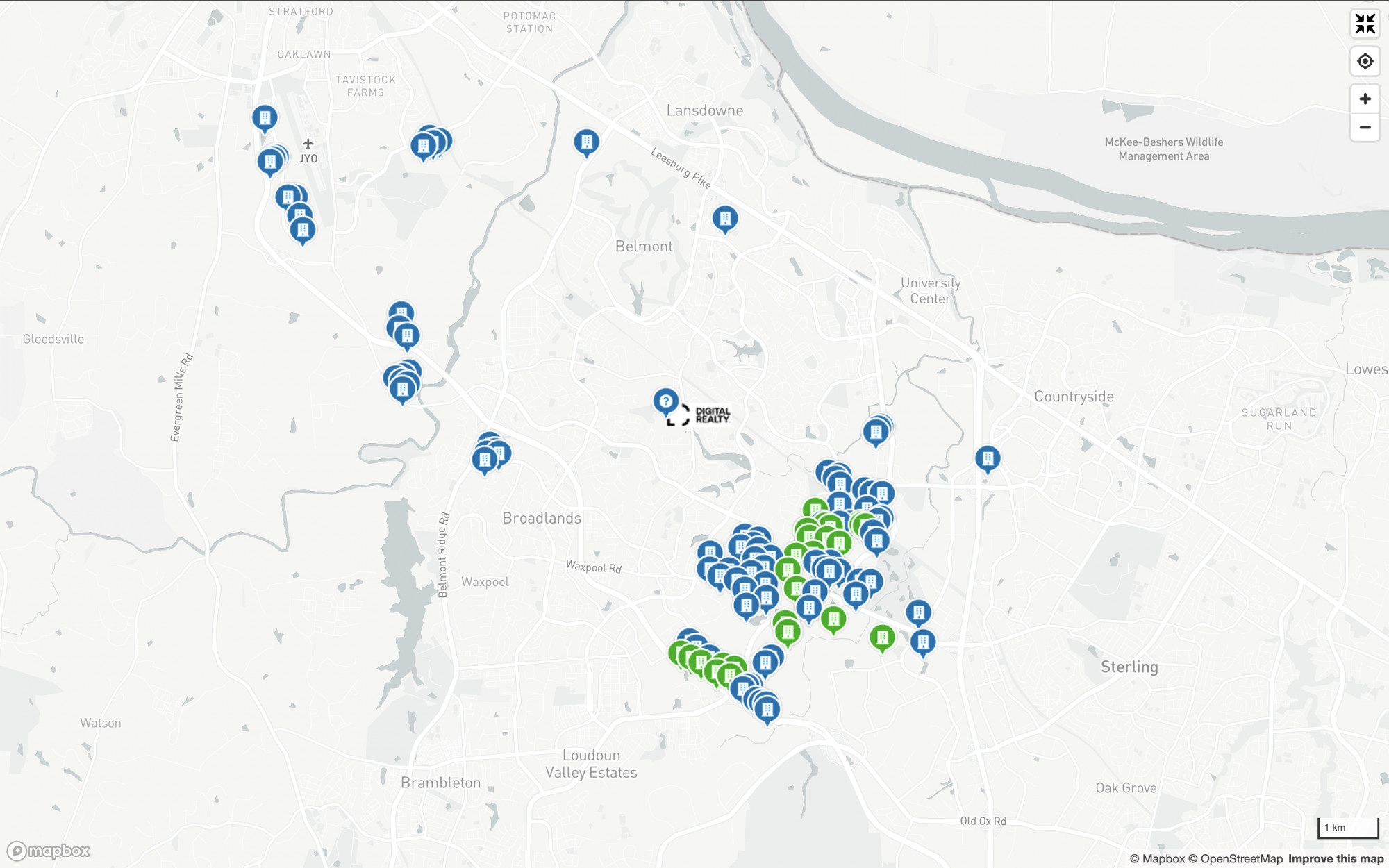

The locations of133 data centers in Ashburn, Virginia, courtesy of DataCenterMap.com

Data centers’ greatest need and greatest expense is power, much of which is used to keep its vast servers cool enough to avoid overheating. This cooling accounts for more than forty percent of electricity usage, and in Virginia, the muggy Mid-Atlantic summers are getting hotter and longer.

“It’s a huge increase in energy demand and a huge increase in supplying it,” says Miller. “And all those impacts should be analyzed up front and not waved away, saying ‘we’ll deal with it later.’ What we want to avoid is the California Gold Rush legacy. Everyone ran out and mined and we’re still cleaning up the mines.”

Dominion Energy—Virginia’s largest electricity provider and the primary electric utility for data centers—is reaping the financial rewards of energy demand. In fact, data centers represent the only growing sector of electricity demand in the state, because of increased energy efficiency elsewhere. In 2023, data centers accounted for nearly a quarter of Dominion’s electricity sales in Virginia, per a Securities Exchange Commission filing.

Data center power needs are projected to more than double by 2040. “We are experiencing in Virginia the largest growth in power demand since the years following World War II,” says Aaron Ruby, Director of Virginia and Offshore Wind Media at Dominion Energy. “Data centers are the largest contributors to that.” But, he adds, “they’re not the only one,” listing off electric vehicles, population growth, and a switch to electric appliances.

Studding the outside of data center buildings are train car-sized backup generators, to ensure unbroken facility operations in case of a main power outage. There are currently four thousand diesel generators permitted for Loudoun County, and all must be tested on a monthly basis. The majority of these generators burn diesel fuel, classified as a carcinogen by the World Health Organisation, producing CO2 emissions.

Keeping the servers cool also requires significant amounts of water. Although data centers have become much more water efficient in recent years, a typical data center still uses as much water as three hospitals or more than two eighteen-hole golf courses.

Most of Data Alley’s major players—Google, Microsoft, and Meta—have agreed to replenish more water than they consume by 2030. But the proposed approaches, such as improved water recycling and using outdoor air for cooling, would increase electricity usage. This is an inescapable tradeoff so far: these Information Age factories can consume less water and thereby use more electricity, or vice versa.

Miller claims Dominion Energy has entered into agreements for proposed data centers without first confirming it can supply the necessary power, all done via a private contract. He has coined a term for it: “crisis by contract.” “There’s a rush to say yes without any analysis of what something at that scale means,” he explains.

Ruby says that this isn’t true. “When we . . . agree to provide electric service to a new large customer, we have to develop infrastructure to do that. That’s not unique to data centers. Any new large user of electric service will need new infrastructure: an office park, residential, schools.”

Despite their demands, data centers generate enormous tax revenue. In 2022, data centers paid $640 million in taxes to the Commonwealth and $1 billion to local governments in Virginia, with fewer service needs than other industries. In Loudoun County, data centers paid approximately $26 for every dollar of local public services they required. Benefit-to-cost ratios for other businesses rarely exceed a four to one ratio.

“All that growth that was residential didn’t pay for itself, we needed something that paid,” explains Bingol. “So, data centers were suddenly this opportunity really for Loudoun.” This is one reason Virginia granted $417 million in tax breaks to the industry from 2010 to 2017. And the industry will continue to benefit from a sales tax exemption on its expensive equipment until 2035.

Much of data center-provided tax revenue to Loudoun County has gone into schools and social programs. The county’s public schools are ranked as the fourth best in the state and boast an ultra-competitive STEM magnet school and a ninety-seven percent overall graduation rate—all while the county maintains a lower property tax rate than neighboring counties.

A county supervisor admitted last spring that “taxes would go up on our average homeowner somewhere between sixty-five percent and seventy-seven percent” without the industry.

Without increased energy capacity, data centers will continue to strain the Loudoun power grid and drive carbon demand. In response, major tech companies are taking the initiative to search for potential renewable energy sources since a lack of stable long-term power is inhibiting their growth. In fact, data centers hold half of the renewable energy contracts in the United States. Microsoft recently signed a deal to reopen Three Mile Island to help power its data centers by 2028. Google announced last October that it will begin purchasing small modular reactors.

By 2039, Dominion Energy’s goal is to have renewables making up fifty percent of its energy mix, though that stands at only ten percent today. “Renewables alone aren’t able to reliably meet our customers’ needs,” Ruby confirms. To help meet this increase in demand, Dominion Energy recently requested permission to revive plans for a natural gas plant.

The strain isn’t just that more data centers are being built, but that the data centers being built are bigger and taller than what came before. The typical data center building in Virginia can now reach ninety feet in height. The smaller, older buildings used ten to fifteen megawatts of electricity per building, while new ones average thirty to forty.

These larger buildings also require more backup diesel generators, often hundreds per new installation, and new miles of high-voltage transmission line suspended over neighborhoods and historic areas.

As real estate prices in well-heeled Loudoun County rise, the data center industry is advancing farther out. The 2,100-acre Prince William Digital Gateway, in Prince William County, to the south of Loudoun, was approved in December 2023 and will use more energy than Data Center Alley collectively uses today. It’s also across from Manassas Battlefield, site of the first major clash of the Civil War.

Other data center proposals suggest the potential for encroachment on cemeteries and state parks. Historical preservationists allege that several headstones at two historic Black cemeteries in Prince William County were damaged from the construction of a data center and a power substation. This past spring, the National Trust for Historic Preservation declared Wilderness Battlefield in Orange County, Virginia, as one of America’s Eleven Most Endangered Historic Places because of a proposed data center development.

Miller states that in Loudoun there are currently ten major transmission lines under review. “Running a big power line over a historic cemetery is not anyone’s preference. That kind of controversy is only going to increase,” he warns.

In rural Fauquier County, many see what’s happening to the east in Loudoun and Prince William as a cautionary tale.

Like everyone else I interviewed, Kevin Ramundo, President of Citizens for Fauquier County, was quick to say he and his organization are not against data centers, “What we’re opposed to is the indiscriminate location of data centers.” The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, which conducts research on behalf of Virginia’s General Assembly, found that one-third of the state’s data centers are within two hundred feet of residential neighborhoods.

He also cited the lack of transparency and oversight into the development process and the industry’s reliance on non-disclosure agreements. There are seven data centers currently in the application stage for Fauquier County. Ramundo describes the approval process as “chaotic.” “They are being approved without an understanding of where the power will be coming from and how they will be cooled.” He says locals have expressed more interest in his group in the past few years, particularly as people realized that transmission lines come as part of the data center package.

McGuinness, also a member of Citizens for Fauquier County, admits to the visible economic success of Loudoun County. “They’ve reaped a lot of benefits if you look at their schools and their libraries. They’re beautiful. But at what cost?”

Courtesy of Piedmont Environmental Council, Hugh Kenny

In December 2023, the Fauquier County Board of Supervisors passed guidelines that limit data centers to two zoning districts and require them to be no more than forty-five feet tall and one mile or less from existing transmission lines.

But Fauquier’s guardrails are an exception, not the rule. There were seventeen bills proposed in the Virginia General Assembly last year regarding data centers, from requiring that new construction be more than one-quarter mile from parks and residential areas to mandatory disclosure of water and power usage at full build-out. Nearly all died in committee; none were passed.

“Richmond doesn’t have an appetite to introduce more reforms,” claims Ramundo, adding, “Dominion has always had a very strong voice at the state level.” Dominion Energy has been the largest political donor in statewide politics this year, with $2.9 million in donations to both parties so far.

Ramundo sees his state as a test case for others. “It’s much more challenging than just what is happening in Virginia, but across this country.”

Across the county, country, and the world. Data analyst firm IDC estimates that in 2012 there were 500,000 data centers worldwide versus eight million today. This results in a game of Whac-A-Mole. If Virginia tightens its requirements—as places like Ireland and Singapore have done—construction will likely move to another area with laxer laws but resulting in the same environmental and energy issues unless online shopping, streaming, social media, digitized archives, search engines, AI, and most online activity cease to be a part of contemporary life.