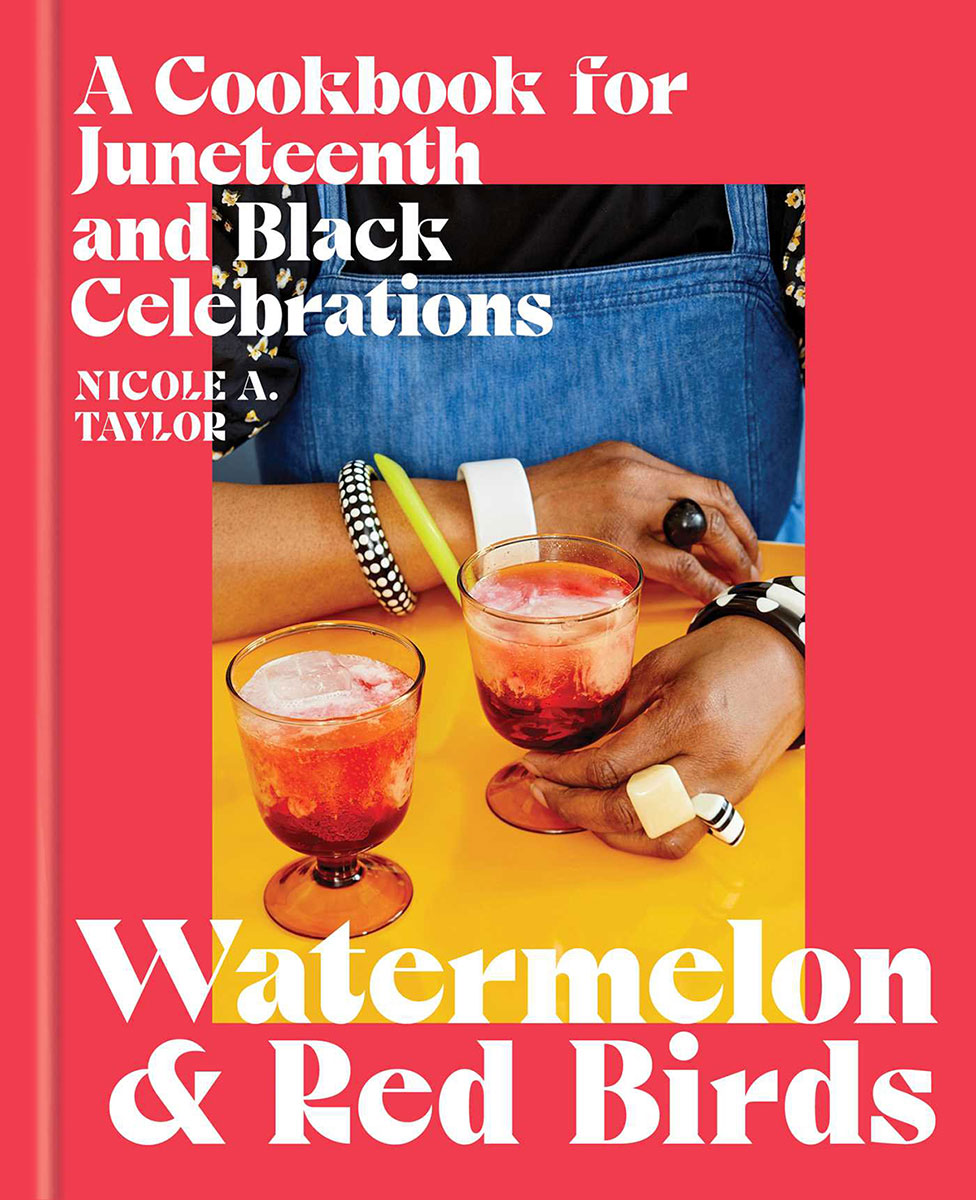

Watermelon & Red Birds

A Q&A with Nicole A. Taylor

By Jasmin Pittman Morrell

Image by Paper Over Board

Years ago, when I first heard about Juneteenth, I stood in the checkout line with my daughter at a Whole Foods in South Carolina. An elderly couple behind me appeared to be of my grandparents’ generation, with skin the hue of warm cocoa, snowy crowns of hair, and unmatched genteel grace. As we waited, they asked my baby’s name. When I told them her name was Jubilee, they grew excited, wondering if I’d named her in honor of Juneteenth. I saw their faces fall when I admitted I hadn’t heard of it. They explained that on June 19, 1865, two years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas to issue General Order No. 3, declaring that all remaining enslaved people were free. “It’s our liberation day, honey,” he said. “We call it Jubilee Day.” I immediately wondered if and how the dessert “cherries jubilee” might be connected to Juneteenth, because don’t celebrations always call for the best kinds of food?

In her latest cookbook, Watermelon and Red Birds: A Cookbook for Juneteenth and Black Celebrations, James Beard Award-nominated food writer Nicole A. Taylor recognizes the way cookbooks can serve as living documents, guiding us to the intersections of memory, place, and generational hope. A Georgia native, her 2008 move to New York inspired her first cookbook, The Up South Cookbook: Chasing Dixie in a Brooklyn Kitchen. She’s also authored The Last O.G. Cookbook and written for the New York Times, Bon Appétit, and Food & Wine. Recently proclaimed a federal holiday in 2021, Juneteenth commemorates Black liberation with cookouts, red drinks, plentiful desserts, and gatherings reminiscent of block parties and family reunions. Taylor uses Watermelon and Red Birds as an opportunity to approach a weighty history with a light touch—her recipes, like Tornado Sweet Potatoes or Afro Egg Cream, sing and welcome joy to exist alongside the persistently triggered sorrow of the Black community in the United States.

Taylor notes the look and feel of Watermelon and Red Birds was inspired by the Alabama-born, Chicago-based artist Kerry James Marshall’s painting, Past Times. Its colorful depiction of Black people picnicking by the riverfront signals a certain carefree jubilance and an invitation to rest. Throughout the cookbook, Taylor highlights the idea that rituals of leisure and care are key ingredients of Juneteenth’s legacy. After that day in 1865, the newly liberated Texans laid a foundation for openly celebrating a story of perseverance, one we’re still building and rebuilding as the nation struggles to set its fractured bones. With entire sections devoted to sweet treats like Snow Cones, Ice Pops, & Ice Cream, and others to the delights found at festivals and fairs, Taylor reminds us how pausing to gather with friends and loved ones disrupts the narrative that labor is the only way of life.

If Juneteenth is about honoring our ancestors’ labor with a commitment to enjoying a sweet potato spritz on a sultry summer day, it’s also about honoring the future with an equal commitment to tell our stories, both in words and through the goodness of food gracing our tables.

Photo of Nicole A. Taylor by Adrian Franks

Jasmin Pittman Morrell: In your introduction, you reference the title of this cookbook–Watermelon and Red Birds–and the old African American and Native American adage that red bird sightings are visits from our ancestors. May we begin in naming your ancestors and the spaces that serve as your creative touchstones?

Nicole A. Taylor: Boley Taylor, my grandfather. Mildred Taylor, my grandmother, whom I've never met. My uncle, Charles Taylor. My great-aunt, who’s like a grandmother to me, Bessie Goolsby.

For a long time, when I was writing this book, I had Breonna Taylor’s mother’s name [Tamika Palmer] on my altar and George Floyd. I don’t think this book would be what it is without them transitioning to another place.

This book happened in a moment of pure sorrow, for me and for Black people collectively. Grounding my family and other Black people, whose names are known or unknown, is at the core of this book. Even though the book is fun…those people who didn’t or don’t get to experience all the liberties both of us have…this book is for them.

In thinking about the idea that the personal is political, I’m also thinking about the notion that the domestic sphere is political. Does Watermelon and Red Birds elevate domestic labor? If so, how does that speak to the politics of this moment?

NT: I hope that in this cookbook, I tried to paint a picture of my life. Yes, I am a Black woman from the American South who prides herself on being in the kitchen.

But I also hope that I point out that there are so many men, or so many people who identify as non-binary who are fully embracing the kitchen, the grill, the baking. I mention Omar Tate, a dear friend and chef. I center him. I center my husband who is a grill master, a fish master. I center Mr. Gaines, from “A Different World.” The Victory Chicken Burger is a callout to Mr. Lou Meyers, who played Mr. Gaines and how Mr. Gaines ran the cafeteria at Hillman College. There’s representation throughout the cookbook that says both Black men and women know their way around the kitchen.

I wasn’t trying to be political, but I was trying to pay homage to the men I see in the kitchen. That can be a political thing. But, I tend to not think of it as much, particularly when I’m entertaining folks and we get around the table. I don’t go that deep.

In your section on “Everyday Juneteenth” you write about honoring the ‘molecules of the ordinary,’ and how that can be a powerful testament to what Juneteenth made possible. In that sense of possibility, what future does this cookbook hope to call into being?

NT: This cookbook was very much about looking ahead. I was not trying to create “the Juneteenth” cookbook. What I attempted to say to all people is that Juneteenth can be a million different ways. We are not a monolith. And Black people are not a monolith. And we also don’t have to be tied to a very traditional African American table to honor our ancestors.

Put in those traditional foods (like sweet potatoes) in a way that’s unexpected. I gave people permission to do that. You don’t have to make sweet potato pie for Juneteenth. You can make a sweet potato spritz. It is okay to celebrate in your own way…It’s really all about your family traditions and what you want to do with them.

How would you say people who are new to celebrating Juneteenth–or folk for whom Juneteenth is outside of their heritage–how should they approach this cookbook?

NT: My recommendation to all Americans who are curious about Juneteenth and want to do something with their family, friends, and loved ones on Juneteenth is to understand [what happened on] June 19th, 1865.

I think for non-Black Americans, find that one special thing to do with your family. Maybe you cook the harissa barbecue ribs [Beef Ribs with Harissa] from this cookbook, and you talk around the table about Juneteenth. Or, you can go to the front of the book and look at all the products listed from beautiful Black-owned [businesses], Indigenous, and other people of color. I do think it’s important for all Americans to pause, recognize, and take some form of food action.

If you’re Black, and it’s your first-time celebrating Juneteenth, go to this cookbook. Use it as a starter. But also, go back to your memory bank and think about your family celebrations and the foods there. There’s so much overlap between this holiday and others.

How is Watermelon and Red Birds in conversation with other cookbooks like Edna Lewis’s The Taste of Country Cooking, or Toni Tipton-Martin’s Jubilee, or your own, The Up South Cookbook?

NT: My first cookbook, The Up South Cookbook, was very much a narrative of me moving from the South to the North. I love and respect Edna Lewis. She left the American South and went North, and her career blossomed in New York City. At the core of who she was, she always wanted to honor Freetown, Virginia, where she was from, and document that. I’m honored to be mentioned in the same conversation as her because it just expands Black people and place.

And I love Toni, she’s someone I would consider a mentor in a very modern sense. She’s the one who brought it to my attention: you’re one of the few voices in Black food that’s from the American South, born and raised. I am from a working-class, northeast Georgia, college town. You see that sprinkled all throughout the book. You see the tremendous impact of living in Atlanta layered into this book. I wanted to make sure Black names and places were in this cookbook. Because cookbooks serve so much more than just cooking.

How did you approach the research for the cookbook, and how did the research inform the narrative that emerged?

NT: In the back of the cookbook there is a section called “Notes on Juneteenth.” This is a “poor man’s bibliography.” I wanted to give people the resources I turned to the most.

When it was time to write the essays and headnotes, my process was two-fold. I listened to a lot of music, Kendrick Lamar, a lot of Solange’s When I Get Home, which has so many references to Houston and Texas. When I got stuck, I would go to record shops. And I remember picking up Mavis Staples’s [We Get By]. On the album cover, there were kids outside in the summertime. [This photo, “Outside Looking In”, by Gordon Parks was originally featured in his iconic 1956 series on segregation “The Restrains: Open and Hidden” for Life magazine. In it, Black children peer through a chain-link fence at a playground where white children are allowed to play.] Seeing that image inspired me to think about foods I had in the summertime—when it was a hot day, and I’d just gone to the pool or left camp. So, I kind of approached the research as an artist. I had to get outside and be inspired by things around me.

I read a ton of Black cookbooks, and if they had any Juneteenth references in the index, I read them. Then I had to go beyond Black cookbooks, like Harriette’s Cole How to Be, which is about Black etiquette and rituals and celebrations.

I would read a little in the evenings [from Black history books], and listen to audiobooks about Black culture and take notes. And some of that stuff would be a jumping-off point…I knew I wanted to include something about The State Fair of Texas being desegregated [to demonstrate that Black people weren’t allowed to participate in the fair until the 1960s], but I wasn’t sure how to fit it in and how not to make it so heavy.

There are a lot of references to Latinx culture since it’s so much connected to Juneteenth in Texas. So, you see nachos, and chorizo and cheese, you see a lot of Tex-Mex. You see the savory elephant ears, which is a connection to Mexican culture and Native American people. And the sumac, which is very much used by Indigenous U.S. folk…I made sure I didn’t just drop sumac in there and then not speak to Native folks and how they use it as well.

What’s on your Juneteenth menu this year?

NT: I’m so excited! I got a new pizza oven from Ooni. I want to attempt to make the savory elephant ears in the Ooni…I’m going to play around a lot. But I will always make sweet potato spritz, it’s one of my favorite red drinks, ever.

This series was published with support from The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.