BIG EARS, A REANIMATION

By Holly Haworth

Big Ears is a strange music festival held annually in Knoxville, Tennessee, that old hometown of Cormac McCarthy, who called the city “obscure and prismatic” in Suttree, in which he populated it with eccentrics, roughnecks, criminals, and squatters. Knoxville is the home of poet R. B. Morris, who has called it “the Bermuda Triangle of Appalachia,” a metaphor that might mean it’s a place that sucks you in, a place in which your navigational instruments don’t work like you expect them to, or a place where weird shit happens, which generally, in my experience living there off and on for fifteen years, seems to hold true. Lying just west of the Appalachians in the broad Tennessee Valley, Knoxville was the first capital of the Southwest Territory and has always been something of a frontier.

Since it began three years ago, Big Ears Festival has hosted some of the world’s great minimalist composers, including Terry Riley, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich, along with artists like the dark-electronic-ambient genius Tim Hecker, the wild-minded harpist and lyricist Joanna Newsom, drone metal pioneers Earth and Stephen O’Malley of Sun O))), no wave/free jazz guitarist Marc Ribot, and a lot of other musicians you’ve probably never heard of. It’s an obscure and prismatic music festival in an obscure and prismatic city, catching the light from all different angles.

The span of these artists is wide, but they are loosely knit by an “experimental” quality—a word that John Cage once obliquely said he used to describe “all the music that especially interests me and to which I am devoted.” This seems the case, too, for the festival’s producer, Ashley Capps, who also produces the more famous and much larger Bonnaroo in rural Manchester, Tennessee. Every year, at the opening festival ceremony, Capps, a Knoxville native, gives a meaningful talk in which he expresses his clear interest in and devotion to the carefully curated music of Big Ears and asks that attendees really use their ears, really listen. “Listening,” he said earnestly, “is something our world needs a lot more of.”

The experimental quality—an approach to art that encourages strangeness, originality, and unexpected associations, that pushes borders and resists categorizations—is the thread that stitches all the disparate pieces of the weekend-long event together. The festival combines musical performances with panels and talks, art installations, film screenings, and interactive workshops, pieced together like Dr. Frankenstein’s monster—the creature made of many parts. Big Ears, Knoxville’s monster, might be one of the most quietly earth-shattering, subtly luminous festivals the world over.

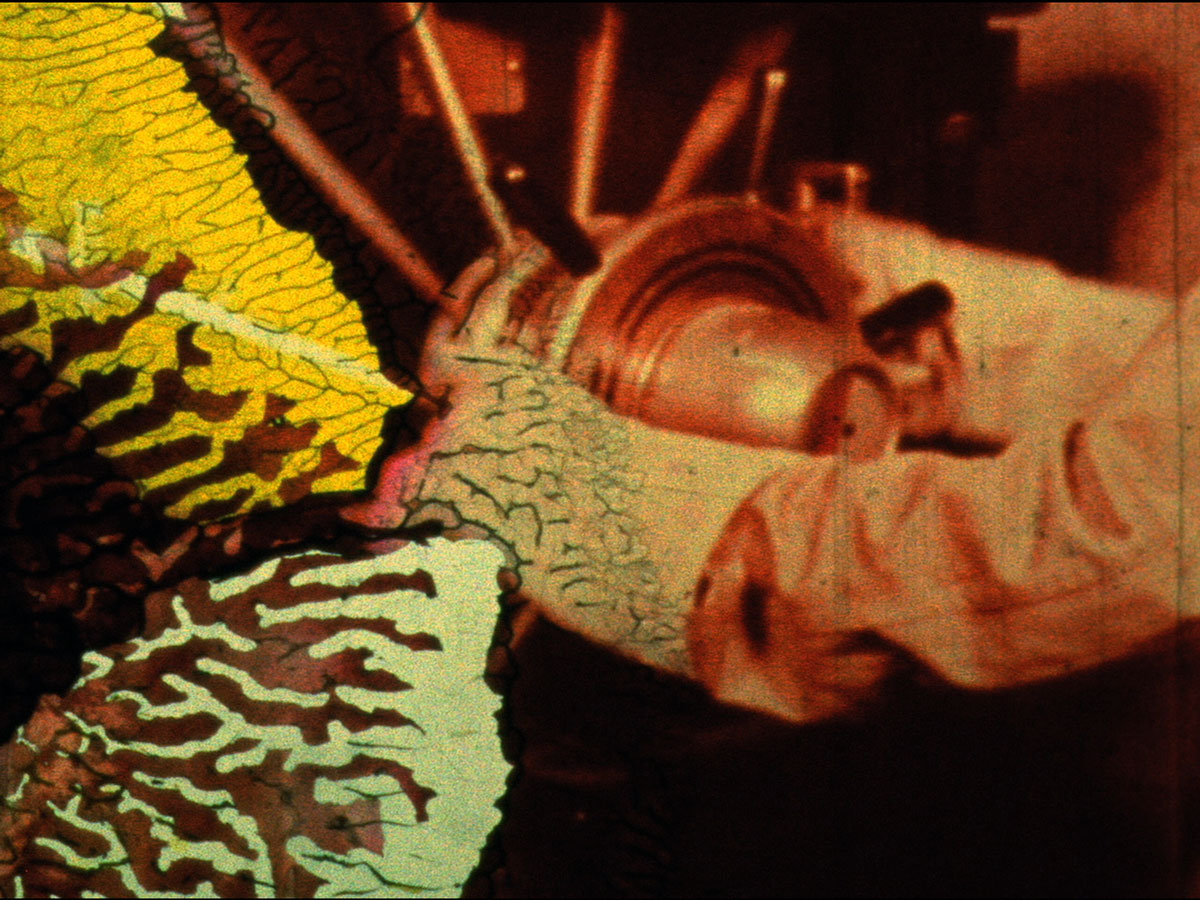

Image from “Spark of Being” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

Image from “Spark of Being” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

The Frankenstein thought began to take hold of me very early on in the festival, when I attended a screening of experimentalist/mad-scientist filmmaker Bill Morrison’s silent film Spark of Being, based on Shelley’s novel, in which the doctor succeeds in “animating” life. To animate comes from the Latin animare (to refresh, to quicken or revive or make to live), and that comes from the original root anima, which signifies air, breath, soul, mind. It means to give spirit or inspiration. To animate can also mean, in film, to make drawings and still photographs come to life with movement by presenting them quickly and in succession. Morrison’s film takes its title from a line of Frankenstein: “With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.”

As part of the new “Big Eyes/Big Ears” aspect of the programming, a handful of Morrison’s films were shown throughout the weekend alongside Man Ray shorts and a series of films from the Criterion Collection, curated by Jim Jarmusch and Michael Gira, who both performed in bands. Introducing Spark of Being, Morrison described how he uses found footage, film that is often decayed and damaged, a kind of exhumation of rotting corpses. “After days and nights of incredible labour and fatigue, I succeeded in discovering the cause of generation and life; nay, more, I became myself capable of bestowing animation upon lifeless matter,” reports Dr. Frankenstein in his account of creating the monster. As much as people discuss Shelley’s book for the compelling ethical questions that it raises, it can also be read as a metaphor of the artistic process: the kind of fever that an artist finds himself in, working long hours in the dark, alone, to make his material, his vision, come to life. Of his own work, Morrison said, “I compiled the creature of disparate parts.”

The theater darkened and the film rolled. One of the first scenes shows a drowning victim pulled from icy waters onto the deck of a ship. Men gather around him, stripping him of his clothing, rubbing his limbs to heat them, pumping his chest, trying to infuse him with life, to bring him again to his senses. The scene is punctuated by the original compositions of Dave Douglas and Keystone, who Morrison commissioned to score the film. Music plays a large part in Morrison’s silent movies, which explore the tension between the aural and visual senses and how each of them inform emotion and narrative in what are only loosely narrative films. In a segment titled “The Creature’s Education,” the film was badly damaged, marked with what looked like mold and water and leaking light. In those strange markings, which reminded me of the folded and eroded terrain shown on a topo map, or like gray matter, Morrison bled colors into changing shapes, purples and lime greens obscuring the lines of boundaries and canyons and bodies, seeping new life into old film. The drums, keys, and brass, which had been contemplative and brooding leading up to the scene, heightened to an erratic fervor. The trumpet cried out, a butterfly fanned its wings, and the speed of the film increased; it was an ecstatic array, a primordial soup, a warm shallow sea of color—nauseating, almost—and then there was a baby born, an egg cracked into a hot pan.

The effect of watching old footage, highlighting as it does the passage of time and the transitory nature of the medium—what Morrison has called “the ravages of time and decay on the filmed image”—conjured memories and feelings of nostalgia, flickerings of a not-too-distant past. I thought of a captivating story from before the advent of moving pictures that I read in local historian Jack Neely’s book Knoxville’s Secret History: Dr. Stephen Foster, an eccentric professor from Greeneville, Tennessee, was “our own Dr. Frankenstein.” Later, while walking between venues, I stopped by the library to re-read the story. Neely writes that Mary Shelley, at the time she wrote Frankenstein, had been particularly interested in the experiments of Italian physicist Luigi Galvani, who made frog legs jump by shocking them with electricity, and Galvani’s nephew, who continued his uncle’s experiments after his death. By applying electrodes to various places on a fresh corpse, he succeeded in making the corpse “open one eye and clinch his fist.”

By 1828, Frankenstein, and the experiments that influenced Shelley, were well-known in Knoxville, and the eccentric Dr. Foster, also a Presbyterian minister, had his own hopes for re-animating a corpse. He constructed a Galvanic cell, a type of electrical battery composed of a zinc anode and a copper cathode, which he kept ready at the Presbyterian church. When two criminals were hanged at the gallows downtown that summer, Dr. Foster was in attendance, waiting. Just when the criminals went lifeless and were cut loose, the doctor loaded the younger of them, a man in his thirties who had murdered his lover’s husband, onto a one-horse cart and rushed to the church, with a large crowd following him. There, he laid out the corpse, hooked it to electrodes that were powered by the Galvanic battery, and applied the circuits. One man stood on the stone wall that surrounded the church, looking in, and reported the proceedings to the crowd that had gathered outside. Suddenly the dead man moved, “breathed once, twice, three times,” writes Neely. “A cheer went up through the crowd in downtown Knoxville.”

Later I would sit in the darkly ornate, historic Bijou Theatre just one street west of that same church, in a building that in the summer of 1928 had been the Jackson’s Hotel, one of the most popular gathering spots in the city. I was there to watch another of Morrison’s films: The Great Flood, featuring a live score by guitarist Bill Frisell. A work that also takes on decay and memory as its primary subject, it is a long-running montage of footage of the Great Mississippi Flood that inundated 27,000 square miles of delta in the summer of 1927. The footage is stunning, reeling and flowing out longer than any typical documentary footage, so that one begins to feel the river, feel the waters rising, as Frisell’s blues-jazz compositions move fluidly with the flow of those images of churning, rising waters. “I don’t know if this is documentary or non-narrative experiment or a prolonged music video for people of peculiar taste,” one reviewer said of The Great Flood. “All I know is that it is gorgeous and haunting and altogether human and important.”

Down the hill from the Bijou Theatre, in the small graveyard to the side of the First Presbyterian Church, Doctor and Reverend Stephen Foster lies buried, his corpse long decomposed. On his tombstone are the words Mysterious are thy ways, O Lord. To the south of his grave and a little west along the Tennessee River sits the local university’s Body Farm, one of the foremost research facilities in the world for the study of the decomposition of the human body. “Like our own bodies,” says Morrison, “this celluloid is a fragile and ephemeral medium that can deteriorate in countless ways.”

Image from “The Great Flood” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

Image from “The Great Flood” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

One of the great joys of a festival like Big Ears is hearing and seeing artists in the flesh. These are creators who spend much of their time in the dark, in bedrooms and caves and basements and studios, writing and recording onto decaying mediums like tape (currently back in vogue), vinyl, and digital (even digital can decay, as technologies and software become outdated, computers crash, and files are misplaced, corrupted, or lost). I remember being stunned at the festival last year when I realized that, even as a music-lover, I had allowed myself at some uncertain point to lose sight of the simple knowledge that music is a bodily experience, created and performed and experienced by the living, sensing body. Hearing a song as it lives in a moment and will never live again—the way it fills the shape of a room, the way it is almost palpably received by the audience—shows how each song, performed, is a kind of re-creation of what it originally was.

Inuit throat singer Tanya Tagaq performed Canadian composer Derek Charke’s mesmerizing Tundra Songs accompanied by Kronos Quartet, the festival’s artists-in-residence. Tagaq sounded like a possession of many spirits, fierce snarling outbursts coupled with fits of moaning passion and wailing pain. Laurie Anderson performed her Landfall, a multimedia and spoken-word piece about the stars, a flooded basement, and disappeared species while Kronos Quartet’s strings circled like the unraveling of thoughts, spinning out Anderson’s words and stories. Australian composer and producer Ben Frost, who has lived in Iceland for the past twenty years, performed a thunderous late-night set that was terrifying and bewitching. Grouper (also known as Liz Harris) performed her densely layered ambient tunes: ethereal, haunting, and yet light-filled and dreamscaped, unfolding in slow movements of luminous loneliness. The onlookers crowded in an attempt to see her, where she sat on a rug on the floor, unlit, just a shadowy form crouched there in the dark among her instruments, dials, and knobs that she slowly moved, twisted, calibrated, adjusted and re-adjusted, creating drifting songs like so much fog, songs that were deeply sad yet illuminated from within. “I’m looking for the place the spirit meets the skin,” she sang.

Ashley Capps’s reminder for attendees to use our ears and open our eyes had seemed at first obvious, but as the festival went on, I noticed an uncommonly earnest attentiveness—a quality I might call a quiet openness—that characterized the audiences as a whole. We were a diverse crowd: sports-jacketed professors and composers; straggle-haired, hoody-wearing kids in their early twenties; lean punks dressed all in black with mohawks and tattoos; at least one man in his sixties with pink-and-blonde hair wearing neon-colored jungle-print pants, a black velvet coat, and purple boots; jeans- and polo-shirt-wearing middle-aged men; bearded and flannelled adventurers; one Hungarian history professor named Csaba who specializes in U.S. utopian studies and the politics of sound; a curly-headed woman wearing a black leotard and knee-high striped socks; a jet-black-haired serious-looking man in a Jodorowsky t-shirt; and Jim Jarmusch, who seemed to be at every show that I went to, with his wild white hair standing out from his head, looking as if it were perpetually electrified. These festival-goers wandered into shows not quite knowing what to expect, only that this would very likely be like nothing they had heard or seen before. A kind of dumbfounded wonder possessed us all.

Image from “Spark of Being” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

Image from “Spark of Being” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

On the last morning of the festival, in the light-filled, airy main hall of the Knoxville Museum of Art, the British post-minimalist composer and pianist Max Richter, Icelandic composer Hildur Guðnadóttir, the acclaimed experimental musician Tyondai Braxton (formerly of Battles), and Ben Frost presented on the topic of “Technology’s Place in Creativity.” Attendees packed into the hall, a robust and lucid crowd for a Sunday morning. Much was said about the use of computers, machines, and electricity, and about how these devices affect the creation and experience of music. This tension is present in the work of many of the world’s most interesting avant-garde musicians who have played at Big Ears, artists like Tim Hecker, Grouper, Ben Frost, Holly Herndon, Loscil, and Demdike Stare.

Frost said he had recently read a study among fifteen- to twenty-one-year-olds revealing that they prefer the sound of a 128-kilobits-per-second mp3 player to the sound of a vinyl record, and they prefer the sound of computer speakers.

Is this a tragedy? The question was asked.

Hildur Guðnadóttir thought that it might be. She mentioned a study that showed that because of children’s excessive use of digital devices (and lack of activities like playing instruments, drawing, or building things), their brains are now becoming underdeveloped in the frontal lobe. This is the part of the brain that is responsible for the voluntary movements of our bodies. It’s also related to memory, attention, ethical decision-making, and societal conditioning and empathy—in other words, the things that make us human.

Will this one day be a world of corpses, or of creatures who, lacking love, more and more deadened to the world around them, turn monstrous?

Image from “Spark of Being” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

Image from “Spark of Being” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

In Frankenstein, the creature, when he seeks to know the world, listens to voices. The word “voice” appears some fifty times in the novel’s text, always with a modifier; the voices are soft, gruff, sweet, feeble, hoarse, mild, dying, cheerful, harsh, kind. They are spoken in sweet accents. They are tranquil, soothing, modulated, dying, smothered, imperious, sinister, soothing, quivering, loud, sweeter than the thrush or nightingale, musical, flowing in a rich cadence, faint, suffocated, encouraging, full-toned, familiar, and dear.

Hearing and listening are two different things. One of them is involuntary and the other intentional, propelled by a longing to know and participate in the world, to find love in it. I think of the drowning victim in Spark of Being, who falls into icy waters and goes unconscious, and the men who attempt to revive him. To bring someone back to their senses is, in one sense, exactly that: to revive a body to consciousness so that it might use the five senses to know and feel the world. It can also mean to bring them back into a capacity to reason and understand. To have your senses about you is to be a participant in the world.

The day after the festival ended, I could not leave the city to return to my home. My car had broken down and I was awaiting repairs; the Bermuda Triangle of Appalachia theory held true. So I was stuck for the day in the city in which I do not now live, the city in which Rachmaninoff played his last recital and in which Hank Williams may or may not have died at a downtown hotel. This city, another body of disparate parts.

I went walking the bright, quiet streets that were warming again after spring’s last cold snap had chilled us over the weekend. I passed under the Intersate overpass where, the night before, after the Swans played the last show of the festival, people lined up in the cold at the hot dog stand and the BBQ truck. I passed the Pilot Light, the small and steadfast club that has nurtured a strong local community of experimental musicians and that hosted the Hello City Festival, an “indigenous companion” that ran alongside Big Ears and featured many artists who make Knoxville their home. I passed street art of bears, two deer locking antlers, and Elvis. I passed a man sitting straight-backed in a chair on the corner of the square in white shirt and suspenders, a straw hat, smiling and looking far into the distance as he bowed and bent a singing saw; a little girl ran up to drop a quarter in his can. On another corner, a man played the Pink Panther tune on his saxophone.

I sat on the square with the torn scraps and crumpled pieces of paper onto which I had scrawled notes in the dark of old theaters and music halls, laid them out on a table before me like so many pieces of skin that I would suture. I thought of the opening of the eyes, the clench of the fist, the breath, one, two, three times, and I wondered what is the force that animates life, that question that Mary Shelley had wondered, too, in her book with so many tones of voices. I sat looking, listening, and a man yelled from across the square, “If it ain’t makin’ music, it ain’t makin’ no sense!”

Image from “The Great Flood” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures

Image from “The Great Flood” courtesy of Bill Morrison / Hypnotic Pictures