“I’M NO STRANGER TO THE RAIN” BY KEITH WHITLEY

By Alex Taylor

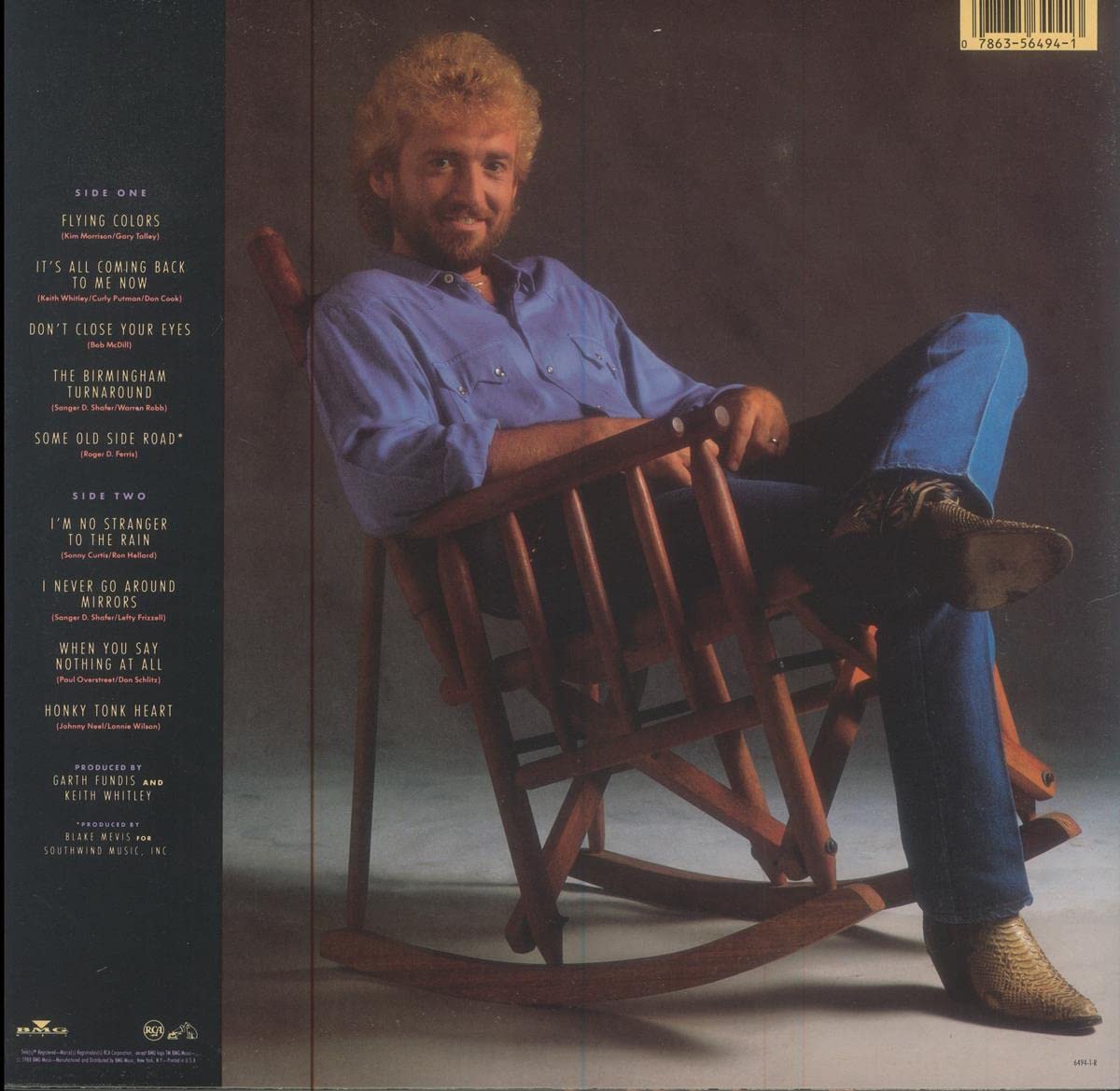

“Don’t Close Your Eyes” album sleeve (back), 1988.

In addition to more than twenty profiles, essays, interviews, and tributes, the 2017 Kentucky Music Issue comes packaged with a 27-track CD, with accompanying liner notes to the songs in the magazine. And since we couldn’t include every great artist and song from the Commonwealth, in anticipation of the issue’s November 21 newsstand launch we’re pleased to present a series of web-exclusive liner notes to recognize even more of Kentucky’s rich music legacy.

From the first drizzly arpeggios, Keith Whitley’s “I’m No Stranger to the Rain” enshrouds the listener in a timbre mysterious as mountain mist. Whitley, who possessed a voice of such rich tonal quality he was among the vanguard of neo-traditional country artists that included Vince Gill and Randy Travis, died of alcohol poisoning only a month after the song reached No. 1 on the Billboard Charts in 1989. Not surprisingly, the opening vocal notes have the air of someone who is trying with great difficulty to swallow their despair. What follows is a melody both ghostly and manifestly physical as Whitley glides between a pained falsetto and thunderous baritone, a sound likely not that different from what Jacob must have heard when he beheld the angels of the Lord ascending and descending their numinous ladder.

Raised in Sandy Hook, Kentucky, Whitley grew up admiring country greats Lefty Frizzell and George Jones, whose vocal styles he imitated as a young musician. Whitley’s uncanny talent for mimicry is something of a legend around Nashville—he could, upon request, conjure with eerie precision the voices of Lester Flatt, Carter Stanley, and numerous others. He was, apparently, a man inhabited by an indwelling of spirits.

This stands to reason, as the Appalachian Mountains where Whitley was reared are a place beset by ghosts. To label them haunted is facile. More accurately, they are a keep for the primeval. Along the sandstone bluffs and hogback ridges of Eastern Kentucky—among some of the oldest geologic formations on the continent—grow rhododendron and mountain laurel shaded by balsam fir and looming hemlock. Carpeting the ground are mosses and ferns of nitric green, as well as beds of flowering perennials such as enchanter’s nightshade and rock skullcap dotted up with purple blots of dog violets. Some species of ephemeral flowers in the region are found nowhere else on the planet. To set foot inside an Eastern Kentucky forest is to enter a world where time is measured by the eon rather than the hour. It is little wonder then that while “I’m No Stranger to the Rain” was recorded when Whitley was in his early thirties, it sounds like a song sung by a man much older.

While Whitley honed his style listening to Hank Williams and other honky-tonk masters, it seems likely the land of Kentucky itself was just as pivotal in aging his voice. Musicologists have often theorized that the “high lonesome” sound so peculiar to bluegrass music developed in part due to the fact that denizens of Kentucky lived in such close proximity to a wilderness that offered its own special acoustics. Bill Monroe was said to have learned to sing tenor (at least in part) by listening to the ballads sung by soldiers returning from World War I reverberate from the railroad tunnels near his boyhood home in Rosine. And it is well documented that harmony vocalists from Appalachia improved their technique by hollering and then bending their voice against its own echo as it returned back to them from a thrumming depth of hills. To take as teacher a landscape so soaked in the reverb of memory—memories so ancient that they often transcend the human to attain the status of the supernatural—could not help but make a man old in his heart.

It seems almost certain that a young Keith Whitley would have spent a considerable amount of time in Laurel Gorge, a deep and narrow chasm just outside Sandy Hook. Standing at its summit, one is given a hawk’s view of the world: a landscape undulating outward in verdure of such thickness it seems immortal, hallowed, and broodingly sentient. Descend to the base of the gorge and the perspective is much different. The air is cooler, as if having been breathed from a cave. Along the scarp are stands of clinging juniper and hawthorn trees. From somewhere softly tolls an almost ceaseless drip of water. Like all sounds in Laurel Gorge, this one trembles outward and then retreats, as though writing a tentative time signature across the airy mountaintops overhead. In such a place, it is not difficult to make a study of one’s doom.

Similarly, mortal intimations are heard with clarity in “I’m No Stranger to the Rain,” a song ostensibly about fortitude and endurance, but which is actually a doubt-filled dirge sung by a man in extremis. One has the sense Whitley sings from deep inside a hole, and that he has patterned himself after and counts as kindred the oldest masters of loneliness: not only Hank Williams, but dismal creeks, weed-choked headstones, falling sparrows, the maddening moon.

But who is he singing for? Lyrically, the song contains a reference to the pattern of resilience: “I’ll put this cloud behind me / that’s how the man designed me / to ride the wind and dance in hurricanes.” However, this is quickly followed by a chorus that acknowledges a failing faith in such divine schemes. In this sense, Whitley’s truest kin is Jacob, son of Isaac, the man who found for a pillow a stone and who wrestled with an angel an entire night, a man who, to borrow Walker Percy’s phrase, actually “grabbed aholt of God.”

Ultimately, a singer of Whitley’s caliber demands, even to the point of his own death, that the recreant heavens be stirred, shaken, and finally apprehended, if only briefly, through his suffering.