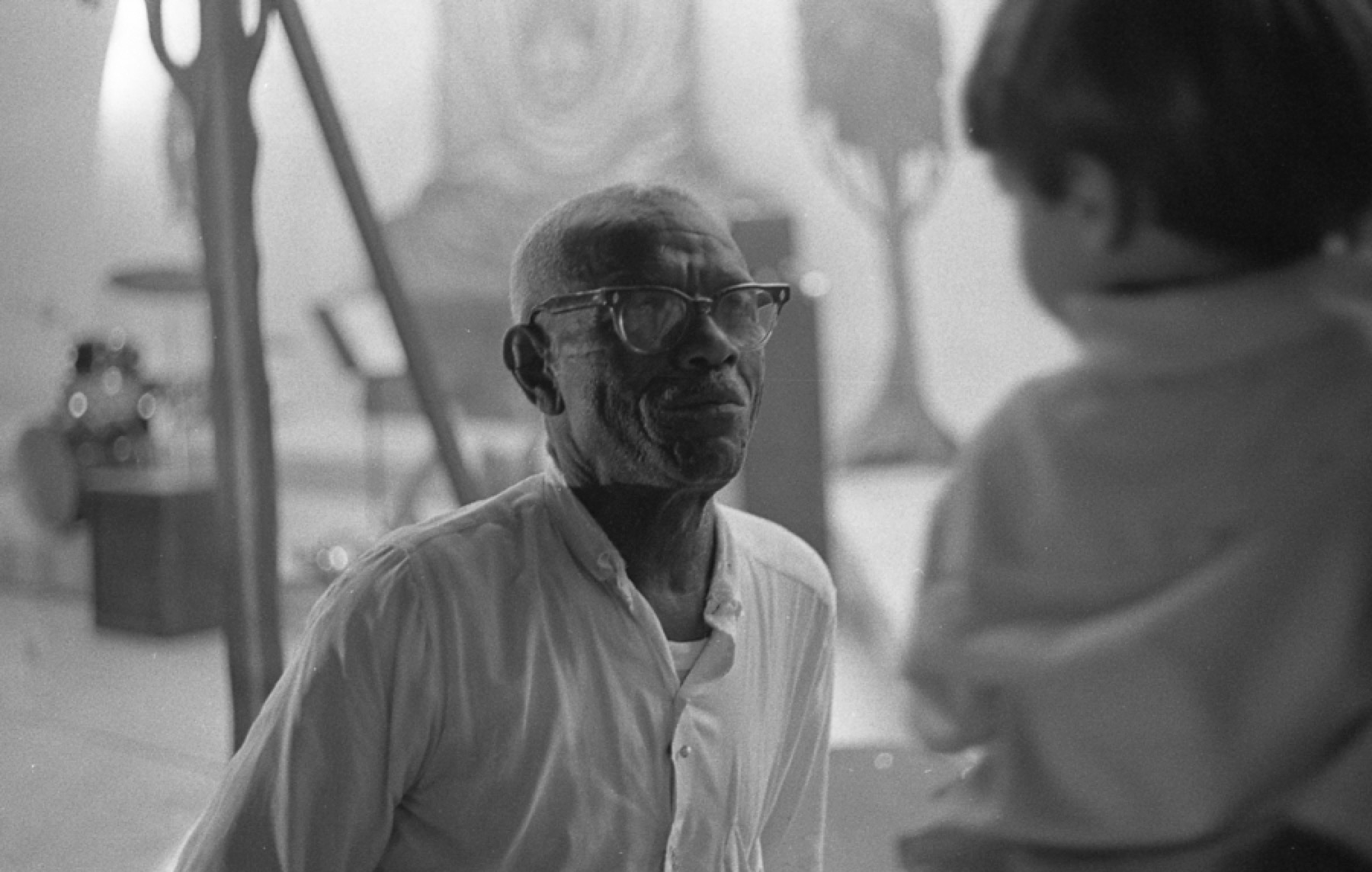

Furry Lewis. © Douglas Cupples, courtesy of the artist

REMEMBERING THE BLUES SOCIETY

By Jay Jennings

As Robert Gordon recounts in his terrific book It Came from Memphis, the Overton Park Band Shell—now known as the Levitt Shell—hosted a Ku Klux Klan rally in the summer of 1966, a week before the first Memphis Blues Festival, which featured an integrated roster of acts, including Bukka White, Sid Selvidge, Furry Lewis, and Jim Dickinson. Memphis at the time was a hotbed for both racial violence and racial coalescing around the brilliance of the blues. Four hundred showed up for the Klan rally—hooded and hidden, lit only by the flames of a burning cross (and, it must be said, heckled by protesters). Days later, more than a thousand people paid to attend the festival, held in the full light of a sweltering sun, and as Gordon puts it, the “corporeal spirituality of the blues musicians was as gripping as their music.” The weathered black faces singing onstage and the white faces nodding to the hard-won notes eclipsed anonymous hatred. For the four years the festival was held, those two poles of energy in Memphis of unifying music and racial discord would continue to face off, especially when the 1968 festival was held in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination.

The Memphis Country Blues Festival (as it came to be known in succeeding years) had a shoestring start, organized by the Memphis Country Blues Society, an ad hoc group consisting of counterculture figures, musicians, and fans, including Robert Palmer, who would go on to write the seminal book Deep Blues and become the first pop music critic for the New York Times. His daughter, Augusta Palmer, a filmmaker and professor at St. Francis College in Brooklyn, New York, is seeking to tell the story of the festival in a documentary called The Blues Society. You can see a trailer for the film here and contribute to its crowdsourcing campaign here.

She will appear at the newly renovated Levitt Shell on September 8 at 7 p.m. to show rare clips from the festival and participate in a panel discussion with Gordon and others on the 50th anniversary of the first event. “These celebrations mean a lot to me personally,” she says, “because both of my parents were involved in organizing the festivals. My mother, Mary Branton, made an impassioned speech in 1969 begging people not to gate crash because the concerts were intended as a benefit for the aging blues musicians, and she also did beautiful drawings for the 1969 program cover.”

As we put together our own issue on the blues (which you can preorder here), we continue to be amazed at the breadth of its reach and history, and we encourage you to support this event, this film, and others like it that seek to preserve the legacy of the music and its voices.

Enjoy this Notebook? Subscribe to our newsletter.