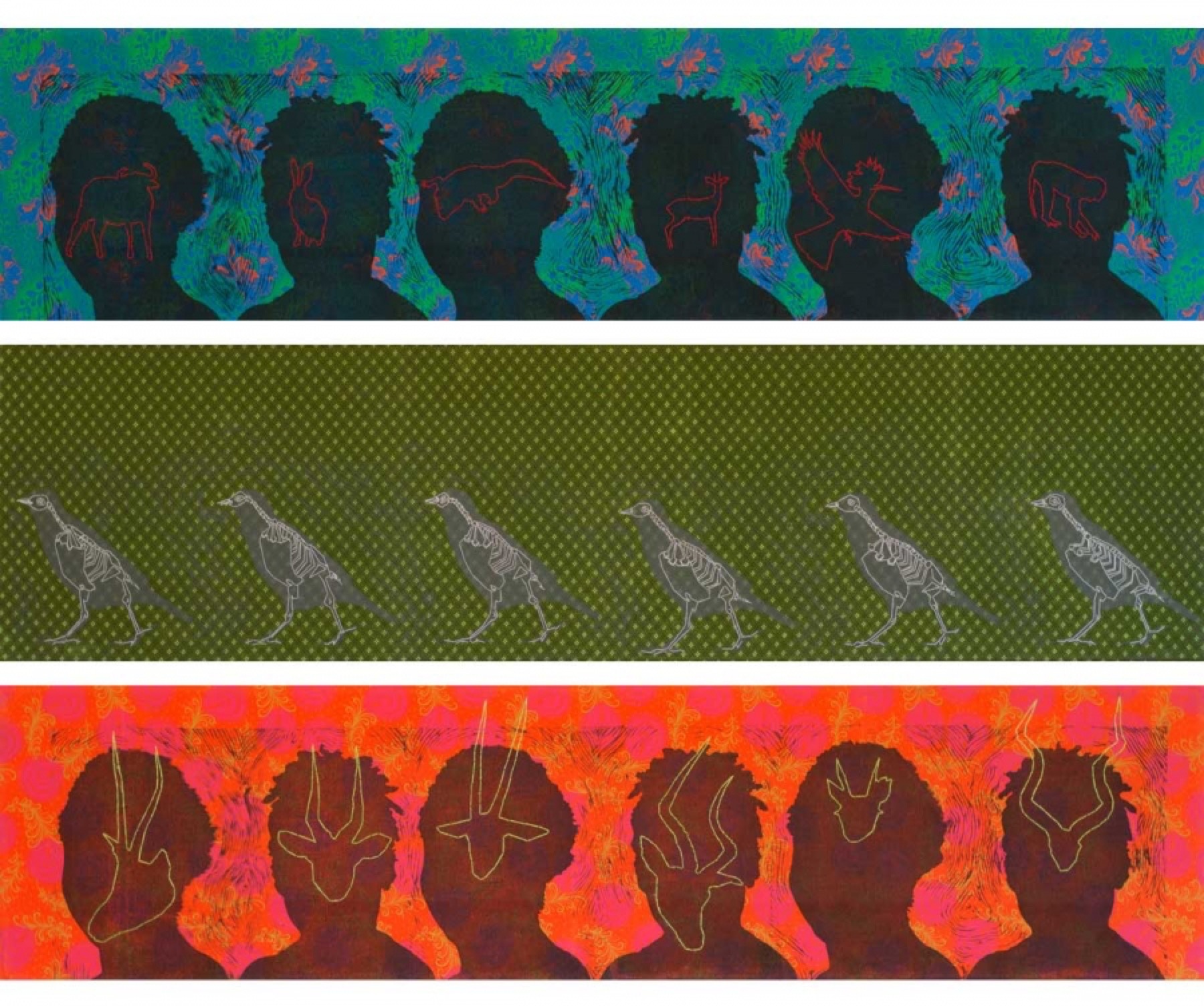

questions by Ann Gollifer | www.anngollifer.org

SOUND AND SILENCE

By Kelsey Norris

A conversation with Gothataone Moeng

Gothataone Moeng’s “Botalaote Hill” opens with a ruckus. The short story from our summer issue clangs with gunshots and kitchen pots and a multitude of voices. And yet—despite this busy and full world—the story feels quiet, too. There’s a hush and a comfort to “Botalaote Hill” that comes, for me, from memory.

As a Peace Corps volunteer in Namibia, I taught at a majority Setswana-speaking school in a village close to Botswana’s border. When the story’s young narrator mentions fat cakes and vinegary chips, my mouth waters with envy. When she says “sharp” in passing, I recall how long it took to learn that the phrase could mean hello or okay or see you later. While I mastered that greeting with time, my tongue was always too slow and clumsy to mimic the ululations that trill through Moeng’s story.

I had the opportunity to speak with Gothataone Moeng, a writer from Botswana and recent graduate of the MFA program at the University of Mississippi. We talked about the role of explanation in fiction, shame, and the power of using sound to “chart emotional tone.”

“Botalaote Hill” is full of setting-specific details. Terms like “Coloured” and “Voetsek” make me think about Toni Morrison’s “lobby” concept—the choice to build scaffolding and introductions into stories for outsider audiences, or to leave them out. How did you choose which elements to explain for a non-Botswanan audience, versus an audience who would immediately recognize the world you’re describing?

I think of readers as being on a spectrum. On one end of the spectrum is the reader who will understand all the specific Serowe and Botswana details and cultural connotations, and this reader is likely to be from Botswana. On the other end of the spectrum is the reader who is perhaps encountering this culture and these details for the first time—likely a reader from outside Africa. In between, there are readers who might understand some details, some of the cultural connotations—so maybe from Southern Africa, the rest of Africa, and the African diaspora. Excessive explaining to the reader who is encountering these details for the first time signifies very strongly to the reader on the other end of the spectrum that the story is about her but not for her.

The scope of my work is very small and place-specific. I write about Botswana and mostly about my home village of Serowe. It would be a shame for me to mine this place and the people therein for stories and then intentionally alienate them as readers. So while I do try to make the story as legible as possible, I also rely on the universality of the themes I am dealing with and hope that is enough to carry a reader—even if they don’t understand specific details, such as the ones you mention. I am also okay with recognizing that some readers will not understand absolutely everything in the story and I actually take advantage of that in some stories, by supplanting sort of “inside jokes” that I know only Botswanan readers are likely to appreciate.

I ultimately don’t think that it’s fundamental that every reader understands every detail of the world of the story because that is not how the world works. We all move through the world with some uncertainty and some vulnerability, and that is okay.

In a similar vein, you include a fair amount of verbal slang (“Ao,” “wena,” “sharp”), especially when young characters are speaking.

When I retain these kinds of words, especially in dialogue, it is usually because I am trying to stay faithful to how people talk, although it is very difficult to do so in translation. Often, I will keep the words in Setswana both because people use English and Setswana interchangeably—often in the same sentence—and also because sometimes those words, translated, wouldn’t make sense.

There’s such an audible quality to this story, particularly in the wedding scene at the story’s opening, the choir scene, and the prolepsis at the end in the narrator’s home. And then, by contrast, Boikanyo and her new boyfriend’s moments in the cave, and the scene after the patient passes—those feel hushed. Do you think about that quality of sound when you’re writing a story?

This is an interesting observation and question, one that I am not sure I can adequately answer. I wasn’t consciously creating this dichotomy between “audible” and “hushed.” It’s more that the circumstances of the story lend themselves to those qualities. The only place where I was really thinking of the “hush” would be when the women—the narrator’s mother and her peers—go into the patient’s room and become quieter in this sort of reverent way that shows both their respect for a person on the verge of leaving the physical world and, I guess, their awe at what illness is capable of.

In some ways, I was interested in showing quotidian joy and the narrator’s family’s participation in it, even as they have a dying relative—maybe as a way to show how these different emotions all co-exist and have a place. I am reluctant to veer too far into “Africans joyful even in the midst of pain” territory, but I do find that there is a pragmatic collective management of emotion in Setswana culture that I am not sure I can explain. Joy and sorrow are communal and have a time and place. This can be pragmatic in anchoring people going through something difficult but doesn’t necessarily allow for individual processing of emotion. So maybe I wasn’t using sound to capture place—although I absolutely think sound is important in capturing place—but more to chart emotional tone.

There’s also a sort of hush surrounding “the patient” and naming the sickness that takes her. When the period of loss that took her aunt and others is mentioned toward the end of the story, the epidemic isn’t specified. Is that silence a conscious choice?

The silence regarding the illness is a conscious choice. I think this goes back to the question of how much to explain and how much readers can pick up from context. Any reader who understands or knows anything about the social landscape of Botswana over the last two or three decades will immediately be able to understand that the illness is likely to be an HIV/AIDS-related illness, which is essentially confirmed much later in the story when the narrator speaks about the large number of people who have died. Botswana was, at some point, the country with the highest HIV prevalence rate in the world. Before the government made ARV drugs free and available to those who needed them, the number of people who died was really horrifying. A common refrain at that time was that even though not everyone was infected, everyone was affected. Especially since we are a country with such a small population—only just over two million at the last population census in 2011.

I don’t mention HIV/AIDS in the story because I think the illness is obvious, and also because it feels accurate that it would not be named. Especially back in the nineties, before the introduction of ARVs, there was a lot of shame and stigma not only for the people who were dying but for the families as well. We are also a culture that really keeps its secrets and has very specific ideas about what information is accessible to whom. So I think while the parents, for example, may have talked amongst themselves about what the aunt is really dying of, that information would not be discussed with Boikanyo and her cousin—although they would be able to figure it out.

The way Boikanyo refers to her aunt as “the patient” in the story also seems like a way to distance herself.

You’re right that calling the aunt “the patient” creates a distance, but in Setswana culture it’s also common to give people titles for whatever they are going through. If somebody is getting married, for the period leading up to their wedding they will be called “monyadi” (bride/groom). A new mother will be called “motsetsi” for the first three months after she has a child. So, calling the aunt a “patient” is not just a narrative device to create distance, but also a part of the culture.

I should also say here that while I keep saying Setswana culture, I am thinking more specifically of it as practiced in Serowe. Setswana culture is not as homogenous as we like to think it is.

I’m detecting some anger from Boikanyo toward her aunt. How much of that has to do with shame, or a feeling akin to that?

Yes, Boikanyo is absolutely angry with her aunt. I think in some ways, the anger becomes the most accessible emotion to her because she doesn’t really know how to feel. She is ashamed of her aunt, and she is ashamed of her shame. She also feels to some extent betrayed by her aunt, who is a sort of glamorous, aspirational figure for her, and has now become a burden whose presence threatens to prevent Boikanyo from leaving the domestic space.

In this coming-of-age story about a young girl in a new relationship, there’s little consequence to the first time the narrator has sex. After that day, the relationship is hardly mentioned, and Boikanyo doesn’t get caught. What made you choose to deflate that potential conflict?

In the initial drafts of the story, the first sexual encounter was kind of ambiguous; the reader would have been left with the question of whether Boikanyo had actually given consent. It would have implied much more strongly that she was using sex—in an unhealthy way—to attempt to deal with what was going on in her household, whereas in the published version it reads more like she knows what she wants; she is a young girl exploring this side of herself while her aunt is dying. I wanted Boikanyo to both have agency and be unscathed by this first sexual encounter.

Globally, there is a culture of magnifying the significance of the first sexual encounter, especially for women. But ultimately, I think that most people move on unscathed or unaffected. It’s important when you are doing it, and some may look back with nostalgia, but for most people, it’s a blip in the larger trajectory of life, in which you deal with bigger matters, like your career and creating a life you want. Of course in these circumstances, there is a threat of contracting an incurable disease, but I think deflating that conflict helps the story become about much more than the narrator’s sexual choices. It becomes more about what this period of time meant for her and for the country. It becomes more about this collective trauma.

Another reason is that to some extent, the story implies that the aunt was sexually liberated. I was wary of the story being read as punishing two female characters for their sexual lives.

I wonder, too, about the moment when the narrator is nervous about the scent of condoms lingering on her skin after that first sexual encounter. It made me think that in this initial experience, she’s practicing both decisive and safe sex.

As a fifteen year old, Boikanyo would have access to sex education—perhaps better access than her aunt, actually. Specifically, sex education focusing on preventing HIV infection. It would be much more of an instinct for her to use condoms, just because it was all over the radio.

I am not sure if that necessarily distinguishes the narrator from her aunt, since that would imply the aunt wasn’t protecting herself. This would raise the question of how she got infected, which I think is often way more complicated than just failing to use protection.

Right; it’s not that simple.

Anything involving sex and emotion gets mired in complications.

Is this story part of a larger project?

I am finishing a collection of short stories titled Small Wonders. It’s set in Serowe and Gaborone, the capital city of Botswana. “Botalaote Hill” is part of the collection.

Read “Botalaote Hill” by Gothataone Moeng, from the Summer 2017 issue.

Enjoy this interview? Subscribe to the Oxford American.