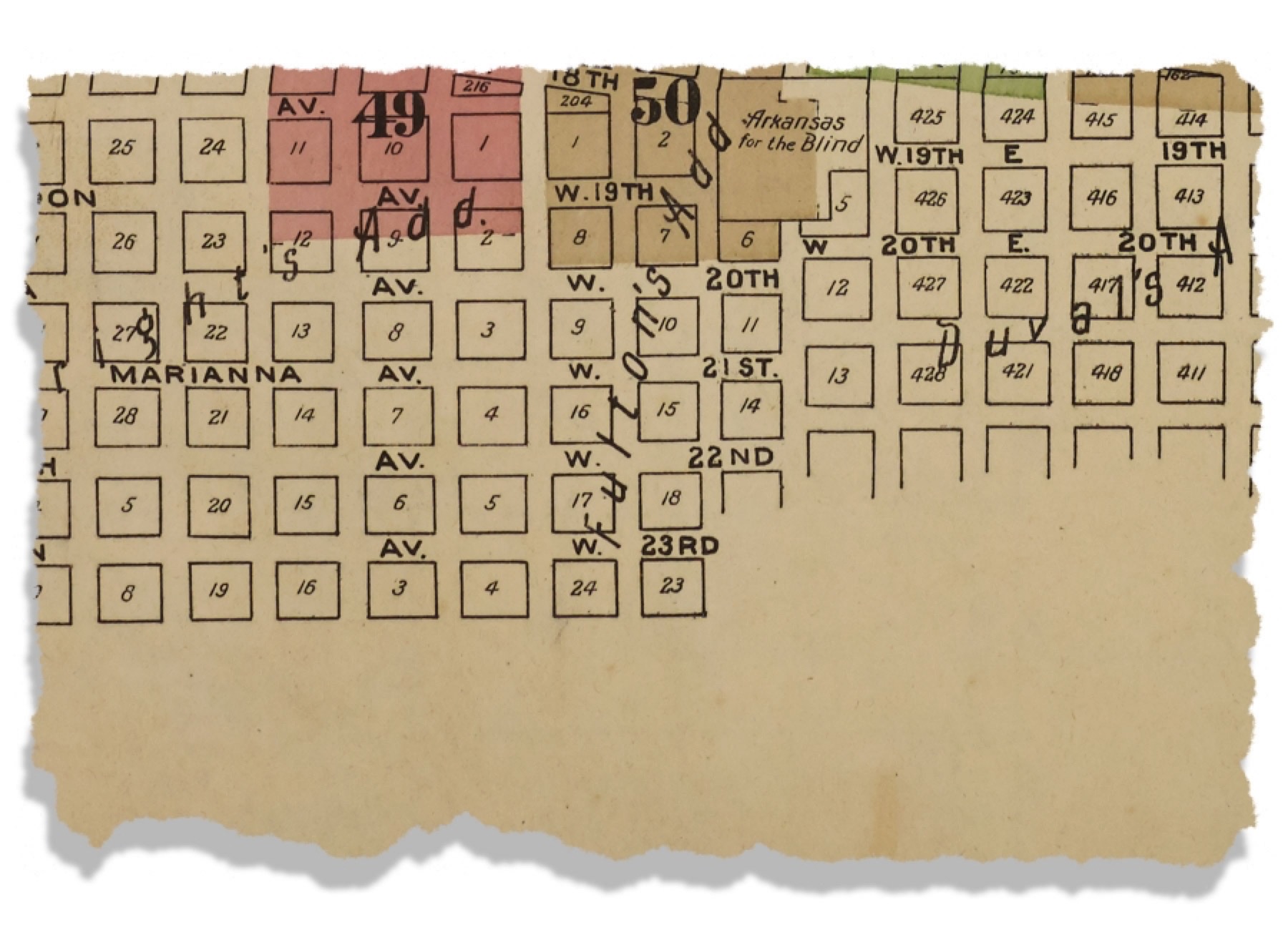

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Little Rock, 1897. The map ends just north of the South End. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

THE SOUTH END

By Frederick McKindra

All Around Us

I’ve lived the past year in the home where I spent my childhood, a four-bedroom ranch house my father bought in 1977 in a predominately black neighborhood in Little Rock known as the South End. My mother joined him after their wedding in 1978, and my family has occupied that same house ever since. One block north, on the other side of Roosevelt Road, sits the Quapaw Quarter, the city’s district of historic homes, and north of that is downtown Little Rock, the city’s urban zone, which runs right up to the Arkansas River. Throughout much of my adolescence, downtown emptied after business hours.

I’ve long struggled with my feelings toward the South End, having never loved the place the way I thought I should. Both my parents rhapsodize about the segregated black communities of their origins. But whereas their tales communicated the wills of their neighbors to persevere, my community seemed intent on trumpeting its hardship. My relationship to the blocks from 25th Street down to the train tracks at 36th has mellowed over the years, from simmering hostility, to indifference, to a fondness that derives from nostalgia mostly, and so sometimes seems too facile. Much of that trajectory was informed by popular depictions of black community, defined throughout much of my lifetime as a place meant for escaping. I bore some guilt for having harbored those fantasies at times, for longing to abandon it.

In junior high school, a classmate once confronted me about this, asking why I didn’t represent the South End the way one was expected to back then, bellowing the name of one of the city’s black neighborhoods—East End, or Hangar Hill, John Barrow, or Southwest—and thereby declaring myself testament to the place’s toughness, or conspicuous affluence. In the moment, I feigned bewilderment, as though unable to recall ever having been asked to do so outright. I shrugged, hoping to convince him I would have served as a poor representative anyway. But I knew what he meant. Consciously or not, I was guilty of scrubbing those mannerisms the South End’s reputation begged of me, according to my peer’s understanding of its history, from my manner and speech. Implicit in his challenge was our mutual recognition of the judgement I cast on the place. Somewhere along the way, I’d begun betraying my block. He wanted me to know that he knew what I was doing.

Neighborhood reputations—the mythologies of black space that meant credibility and authenticity in the late ’80s and ’90s—are spun for the benefit of non-natives, never quite describing the real place. Growing up, I knew the South End as homes mostly, with scrubby lawns that were merely cut rather than manicured, sometimes diligently, and sometimes less so. I knew it as square churches, and three city parks, crowned by convenience stores and liquor stores at both ends, and a strip mall that has long sustained a beauty supply, though the grocery store it housed in my childhood closed decades ago. I knew it as overwhelmingly, if not completely, African-American, having been so since at least the 1950s. Transients, morphed by life and fatigue, have walked its streets long enough that many of them are acquaintances now, and never seem menacing.The idea of one’s black community as “ghetto” was currency once, but that moniker always struck me as a pose for a place as mundane as where I lived, hardly in need of much championing, at least among black folks. Even the most ominous vacant lots sprung green come spring and became field by late summer.

Robin Means Coleman comes closest to describing the neighborhood I knew when delineating “the ’hood” from an earlier construction of black community—"the ghetto.” She writes in Horror Noire that:

The ’hood then, was . . . a place that had real meaning as it pertained to identity construction and understandings of community. For example, it was a place where Blacks were “real,” authentically Black. While some Blacks “got out” through, for example, work or educational opportunities, sell-out Blacks were those who turned their backs to their relationships with, and memories of, the ’hood. While the ’hood had a difficult reputation, it was still home and viewed as having as much to offer, including making seminal contributions to all facets of Black culture.

My South End challenged the conception of black environments imposed on those communities during my adolescence. The socio-economic diversity I’d witnessed there rivaled the rumors of pervasive poverty and crime I heard. In 2016, the New York Times published an article called “Affluent and Black, and Still Trapped by Segregation,” by John Eligon and Robert Gebeloff, on the factors that drew affluent black professionals back to racially segregated and economically underresourced neighborhoods in Milwaukee: the history of racially segregated housing policies, a desire for community, and a stubborn resolve to see those places revived. I recognized this impulse. Many humble professional offices, a tidy neighborhood association center, and plaques denoting historic sites within the South End survive now, evidence of as much care and diligence as any blights or sore spots. Moreover, the neighborhood contains many family homes that draw people back to the area, for Sunday dinners or cookouts.

As my understanding of the history of the South End and of black communities like it evolved, so too did my relationship to the neighborhood. I came to know it as a former enclave for enterprising black educators that supported two public elementary schools and sat near enough in proximity to serve the city’s black high school and historically black college, as the site of mid-century housing projects that once sheltered nascent families aspiring to one day own a home nearby. I came to know the park where Negro League games were once staged. I too understood how time and neglect and underdevelopment had sometimes made the place appear ahistorical, leaving the neighborhood prey to projections on black spaces as voids, disregarded and abandoned.

Ultimately, the place’s stories wooed me. The collective memory meant as much to me as any of the experiences I had walking its streets. The community contained multiple histories, its stories extending beyond the narratives gangsta rap affixed to it during my early years. If I’ve grown to love the community, it’s not because the place has fashioned me into some hardened thing to be feared. Instead, having gained a historical perspective broad enough to consider the area’s many layers, I’ve grown to marvel at its many guises.

“All Around Us” is a part of our weekly story series, The By and By.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.