Editor's Letter: To the West

By Danielle Amir Jackson

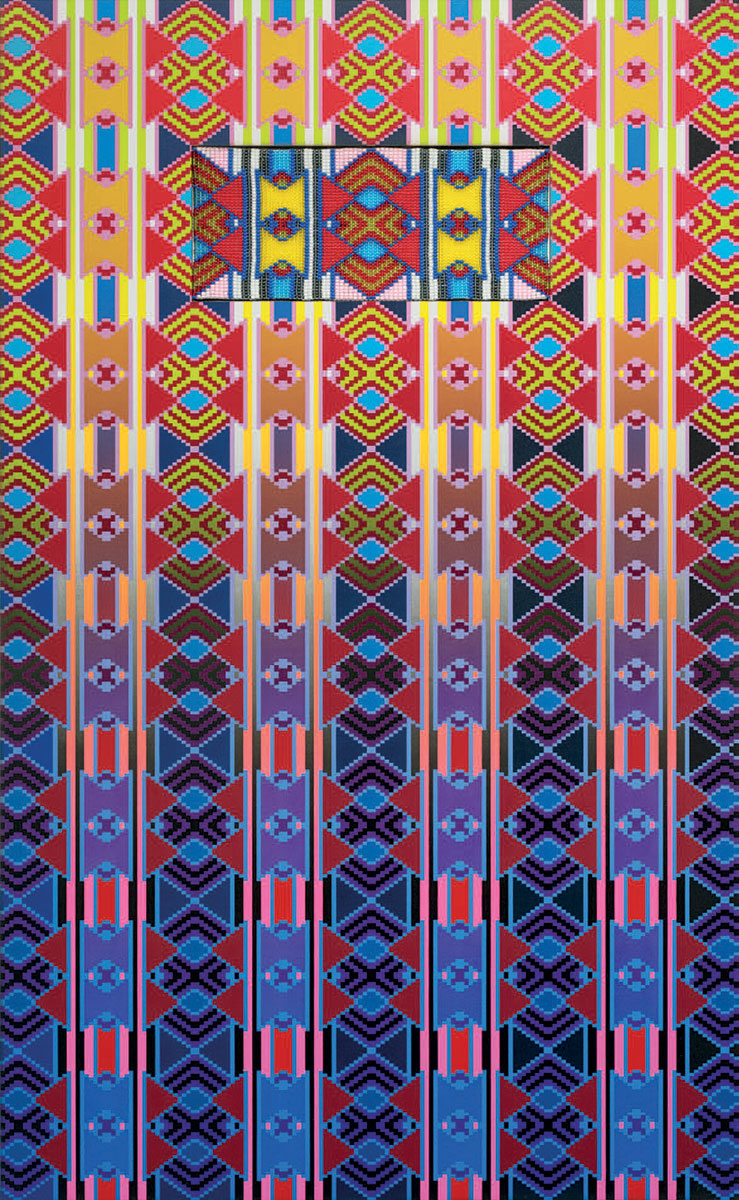

"no simple word for time," 2022. Screen print on Arches 88 mounted to mat board with inlaid panel of handwoven beadwork, by Jeffrey Gibson. Edition of 24; 24.5 x 15 inches. © Jeffrey Gibson, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago; Roberts Projects, Los Angeles; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

In a fourth-grade class on Tennessee history, we learned about the state’s three grand divisions, so distinct one wanted to go its own way during the Civil War. We knew Memphis was westernmost. We were topographically unique: flatter, more swamp-like, with rainy seasons like the tropics. We were tethered to Mississippi, the state and the river, and to the eighteen counties of the Delta. Which meant we looked and ate and sounded more like Mississippi than most of Tennessee. We made barbecue, moonshine, Tina Turner, C. L. Franklin. We were a tambourine and a palm, a double-time piano, a worried line cooed over a bottom-heavy blues.

On a school trip to St. Louis, we learned the city calls itself the “gateway to the west.” Texas, we were told, is bifurcated by the ninety-eighth meridian, which signifies the start of the nation’s westward sprawl. Our part of the South and the West were geographic neighbors, energetic kin—kissing cousins, if you will, sharing land mass and waterways and a constant exchange of people. The borders between us are soft, elastic, permeable.

Our generation played Oregon Trail on Apple IIes and read Willa Cather, whose childhood move from northern Virginia to the plains of Nebraska inspired My Ántonia, a novel I would come to love. My father lived in the Arkansas town where Howlin’ Wolf had been a radio jockey. Back then, the cities just across the river had a reputation. They were raucous, a kind of “wild, wild West” with gambling and fun, untamed parties. They courted an association with the frontier.

Rhoda Bell, my great-grandmother, was born enslaved near Selma. She went west, to Mississippi, when freedom came. There were forests to clear, cotton to tend to, silt-rich soil in which to plant. When Thomas Moss, a postman and co-owner of People’s Grocery near Memphis, was pursued by a lynch mob, his final utterance, according to Ida B. Wells, was, “If you will kill us, turn our faces to the West.” Later, Wells told an audience:

Hundreds left on foot to walk four hundred miles between Memphis and Oklahoma. A Baptist minister went to the territory, built a church, and took his entire congregation out in less than a month. Another minister sold his church and took his flock to California, and still another has settled in Kansas.

During a speech at Brown, Ralph Ellison echoed Wells. “Freedom was…to be found in the West of the old Indian Territory,” he said. Ellison was born in Oklahoma City to parents from South Carolina and Georgia. Maybe some found freedom, for a time: before the massacre in Tulsa? Storytelling about the West is often sentimental, sweeping, fanciful, a rosy impression only slightly connected to reality.

Memphis became a city because the Chickasaw ceded their bluffs—four wooded, rugged hills formed by the meanders of the Mississippi that were dense with green and rich loess soil. Most of Middle and West Tennessee had been carved out of a series of treaties and land grabs by the American government, culminating in Congress’s Indian Removal Act of 1830. People who were Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole and made their homes east of the Mississippi were required to relocate, along with their black slaves, to unorganized territory west of Missouri. Over the next two decades, more than sixty thousand former residents of the Southeast traveled treacherous routes west, through north Georgia, Alabama, middle and western Tennessee, southern Missouri, and almost all of Arkansas. While researching Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville saw the scene in Memphis. “I saw them embark to pass the mighty river,” he wrote. “No cry, no sob was heard among the assembled crowd: all were silent.”

The state parks’ association says Arkansas is “the only state that witnessed the removal of all five of the Southeastern tribes as they moved west.” Pinnacle Mountain, just west of Little Rock, was a key site along the Trail of Tears.

In this issue, frequent OA contributor Benjamin Hedin notes that Quatie Ross, wife of Chief John Ross, head of the Cherokee Nation at the time of removal, is buried in Little Rock’s Mount Holly Cemetery. The legends say she died nearby, on the Trail from Georgia, after giving up her sole blanket to keep a young fellow traveler warm. Hedin speaks to a descendant of Chief Ross and visits the headquarters of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, which sits on the western end of North Carolina. The story, about a soon-to-be published census of the Cherokee Nation before removal, speaks to loss, journeys, place-making, and also what, and who, remains.

The 2020 Census reported growth among every non-white group of residents in the U.S., including Indigenous households. The balmy December I last saw my father alive, we drove past Pacaha burial mounds near the Hopefield Bend Revetment, a levee on the Mississippi’s Arkansas side. He told me a DNA test had revealed an Indigenous ancestor from the 1700s. Hedin writes, “So much of what is written about the Cherokees tends to emphasize removal.” We should remember that the American South has reams of Indigenous history, dead and alive, to recover, and honor, and connect with.

Other stories in the issue similarly reflect on journeys, loss, and the resonant joy that can be found in Southern place-making. Farah Jasmine Griffin travels to the town in middle Georgia where her grandmother grew up. With her immediate family, Ms. Willie Lee Carson had moved North, to Philadelphia, and was less than willing to speak at length about where she’d come from. Still, Griffin says, “the South, embodied in my grandmother, held us together.” Maria Sherman writes about the song of coquis as part of the living soundscape of Puerto Rico, her own ancestral home. Jarrett Van Meter, in his OA debut, travels to a part of Kentucky along the state’s border with Tennessee that is often, quite literally, left off from most maps of the state. He finds a close-knit cluster of families, a beautiful, expanding land mass, and the freshest, best-tasting catfish he’s ever encountered.

We’re proud to present wise and delightful short fiction from Elias Rodriques, Melody Moezzi, and the debut of Meghan Reed of Little Rock. “Where the Animals Sleep at Night,” an enticing mélange of magical realism and traditional realism, caught our eye because of its beautiful sentences, its surreal moodiness, and what it had to say about home, adventure, exile, and the utter unknowability of other people.

The issue also features two pairs of poems, by Mikey Swanberg and Erika Meitner. I love what Meitner writes about space, place, and the human body:

What does it mean to be almighty with joy

of discovery? We can’t sense space without light.

“The sun never knew how wonderful it was,”

Louis Kahn once said, “until it shone on the wall

of a building."