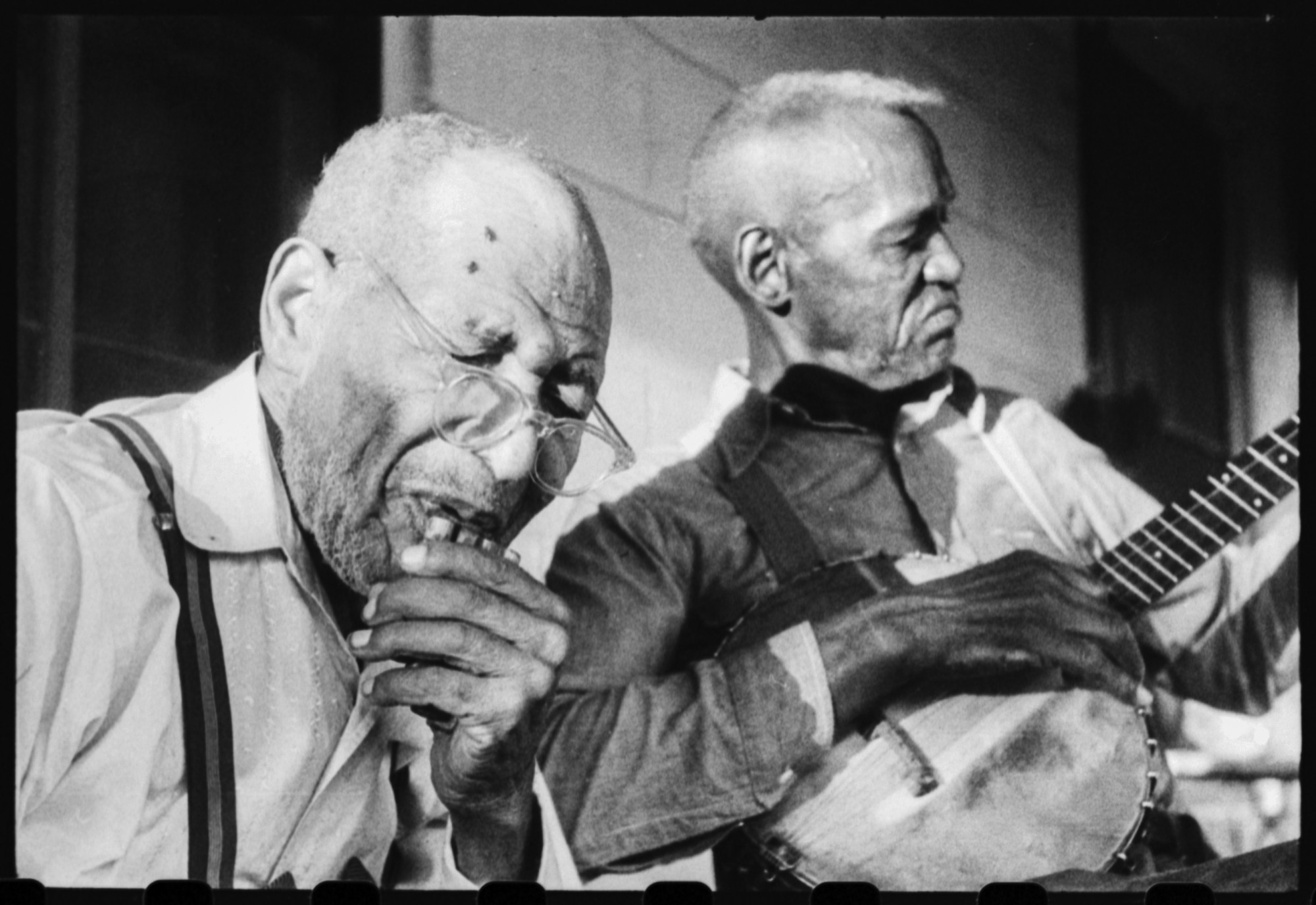

Sid Hemphill (with quills) and Lucius Smith (with banjo) on Hemphill's porch, Senatobia, MS, 1959. From the Alan Lomax Collection at the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress. Courtesy the Association for Cultural Equity

Ballads by Request

Sid Hemphill and “The Strayhorn Mob”

By Jim O'Neal

Alan Lomax, the world’s most famous and prolific ballad and folksong collector and researcher, called the fife and drum music of Sid Hemphill’s band—the first ever recorded by an African American group, in 1942—“the main find of my whole career.” The local fife and drum tradition dated back before Hemphill’s birth in the 1870s and has lived on in the hill country of North Mississippi ever since, led primarily by men who made their own fifes from bamboo cane. The most notable have been Napolian Strickland and Otha Turner, who had both been playing for decades before making their first recordings in 1967. Turner’s granddaughter Sharde Thomas, now thirty-three, carries on the legacy in impressive fashion today, incorporating modern blues, soul, and hip-hop into her performances alongside her vibrant fife tunes. Hemphill’s granddaughter Jessie Mae played drums in such outfits and became world renowned in the 1980s and ’90s as a blues singer-guitarist. Sid Hemphill, who Lomax called “the blind musical maestro” and “the boar-hog musician of the hills,” played many instruments, including fife, panpipes, fiddle, guitar, drums, and mandolin, all of which he made himself—even the drums. He possessed an expansive repertoire.

Lomax and his research partner Lewis Jones recorded Hemphill at a hot, dusty summer picnic near Sledge, Mississippi, at the conclusion of a 1941–42 Library of Congress–Fisk University project that would go down in blues history for capturing the first recordings of Muddy Waters and a historic juke joint performance by Waters’s idol Son House. Fisk professor and musicologist John W. Work III was a crucial contributor to this study, but as it happened, he did not join Lomax and Jones for the Hemphill recording—though he did later transcribe some of the songs.

While much of Hemphill’s music had been passed down through generations, one genre was distinctly of his own crafting: narrative ballads he composed by request. Ballads were the gems Alan Lomax and his father John A. Lomax had prospected for in their years of fieldwork, and Hemphill “was a ballad maker as protean as Woody Guthrie,” Lomax wrote in his 1993 book The Land Where the Blues Began.

The ballads Hemphill recorded were all set to the same basic music and brisk tempo, with Hemphill on vocals and fiddle, accompanied by Lucius Smith on banjo and kazoo, Alec Askew on guitar, and Will Head on bass drum. All were men in their fifties and sixties who came up in an era that predated the blues, which only started to be recognized as a distinct genre around 1910. Hemphill could play what are now known as “blues ballads,” such as “Stack o’ Lee” (aka “Stagolee” or “Stagger Lee,” corruptions of the name Stacker Lee), “John Henry,” and “Frankie and Albert” (popularized as “Frankie and Johnny”). It’s important to note that the term “blues ballad” in later years often referred to the romantic, pensive, or sentimental songs crooned by Bobby “Blue” Bland, Ivory Joe Hunter, and Lonnie Johnson, among others. But there was nothing sweet or soft about Hemphill’s ballad songs. Neither were they slow or relaxed. They were set to lively dance tempos—like the back-country hoedowns that both Black and white string bands once played throughout the South. Still, what truly set Hemphill apart were his original ballads. He was so renowned in the region that both Black and white locals came to him to commission songs about the deeds and misdeeds of themselves or others, or about events worth memorializing. Though the songs were composed several decades earlier, Hemphill had no trouble reeling off verse after verse with fresh enthusiasm when he recorded for Lomax and Jones, his gruff vocals occasionally elevating to a holler as he sawed on his fiddle.

“The Carrier Railroad” or “Carrier Line” described the wreck of a train on the Sardis & Delta Railroad owned by lumber baron Robert Carrier and Carrier’s dispute with the engineer he blamed. “The Roguish Man” was composed for a Black ex-convict known as Jack Castle who wanted his life in crime celebrated. Hemphill recalled Castle exclaiming, “By God, make one ’bout me now, what I done!” The most historically intriguing piece, however, was “The Strayhorn Mob.”

Hemphill said he and “a buddy” (unnamed) composed “The Strayhorn Mob” at the request of Sam Howell, one of the accused troublemakers in a mob that stormed the jail in Senatobia on April 12, 1905. They aimed to lynch a prisoner, Jim Whitt, who had killed Buster Thomason with a double-barreled shotgun on Christmas Eve of 1903. The incident made national news when Sheriff J. M. Poag stood his ground at the jail and was shot and killed by one of the mob, which was composed of relatives and friends of Thomason’s from the Strayhorn community of Tate County, according to newspaper reports. Whitt, a recent arrival in the area, had confronted Thomason, who, according to testimony reported in Memphis’s Commercial Appeal, “had made some remarks that he was having a good time with all the ladies on a certain road. Jim Whitt, hearing of this, believed that Thomason was on familiar terms with his wife.” Whitt was sentenced to hang at first, but the Mississippi Supreme Court granted him a new trial, which prompted the Thomason crew to take matters into their own hands. Whitt was sent to a jail in Jackson for safety, and when thirteen men of the mob were indicted for Sheriff Poag’s murder, those who surrendered or could be rounded up also were dispersed to jails in other counties, with tension running high among the townsfolk of Senatobia. The New York Times called upon Senatobia to erect a monument to honor Poag’s heroism. Some of the indicted Strayhorners, who had fled the scene of the crime, spent time in jail awaiting their trials, but in the end, none were convicted, to the particular dismay of one judge who, according to a dispatch to New Orleans’s Times-Picayune, admonished his jury, “You have disregarded your oaths and trampled the law under your feet.” Whitt was found guilty a second time, but on another appeal he was set free on grounds of self-defense, returning to his former home in Alabama with relief in 1907.

All the principals in this saga were white, and most were described as prominent citizens, although one early report in the Jackson Evening News alleged that there were “nine persons under arrest, five of them being white and four negroes.” Hemphill named several of the mob members, including Sam Howell, who was wounded in the fracas, in his ballad, but that was public information, since those indicted had all been identified in newspaper reports. (Lomax, by the way, misunderstood most of these names; the spellings here are from contemporary newspaper accounts, and the transcriptions are my own.) Hemphill sang of the shooting and the mob’s flight to escape, and he accurately and concisely depicted the circumstances of their trials. His verses included the following:

Them boys around Strayhorn, they didn’t have no job

Went to Senatobi [sic] to head up a mobSome walked ’round the jailhouse, stopped in at the gate

Some of ’em made a shot with a .38When they talk about some runnin’ big boys, runnin’ just like wheels

Oughta been there to see them run, seen Mister Will SinquefieldWell, they’re talkin’ ’bout that mob, hadn’t been nary a one since

Talkin’ ’bout Mister Hunter when he jumped the courthouse fenceThe Strayhorn boys, tell the boys, tell you all a certain fact

The hounds got on the tracks and they brought the boys backWhen they tried the Strayhorn boys they did not try ’em here

Tried the boys most everywhere but they all sho’ come clearWhen they tried the Strayhorn boys did not try ’em alone

Tried the boys most everywhere but they sure come home.

True to his words, the defendants were tried in groups, not alone, and at courthouses in other towns, not in Senatobia. In typical deference of the times, Hemphill called them all “Mister” in his ballad—Mister Sam Howell, Mister Hunter, Mister Norman Clayton, Mister Will Sinquefield. Oddly enough, he told Lomax he couldn’t remember the name of J. M. Poag, the sheriff who took a .38 slug, and never named him in the ballad. Poag’s fate is echoed throughout the song, though, in the refrains “They laid him low.”

Hemphill imbued his ballads, even those about serious topics, with a certain playful lightheartedness. His stories served not only as oral histories but as vehicles to entertain and amuse and to propel dancing feet in the Mississippi hills. His 1942 recordings remained unissued for decades but have since been released on various LPs and CDs, and his entire session is available on YouTube. He died in 1961 after recording a few more songs for Lomax in 1959—but no ballads, which had been consigned to the distant past, never to be heard by most Black Mississippians who had long since tuned in to blues, soul, disco, funk, jazz, hip-hop, or gospel. The city never built a memorial to its murdered sheriff, despite all the furor of the times, and it was Sid Hemphill who was honored with a historical marker in Senatobia, placed by the Mississippi Blues Trail in 2017.