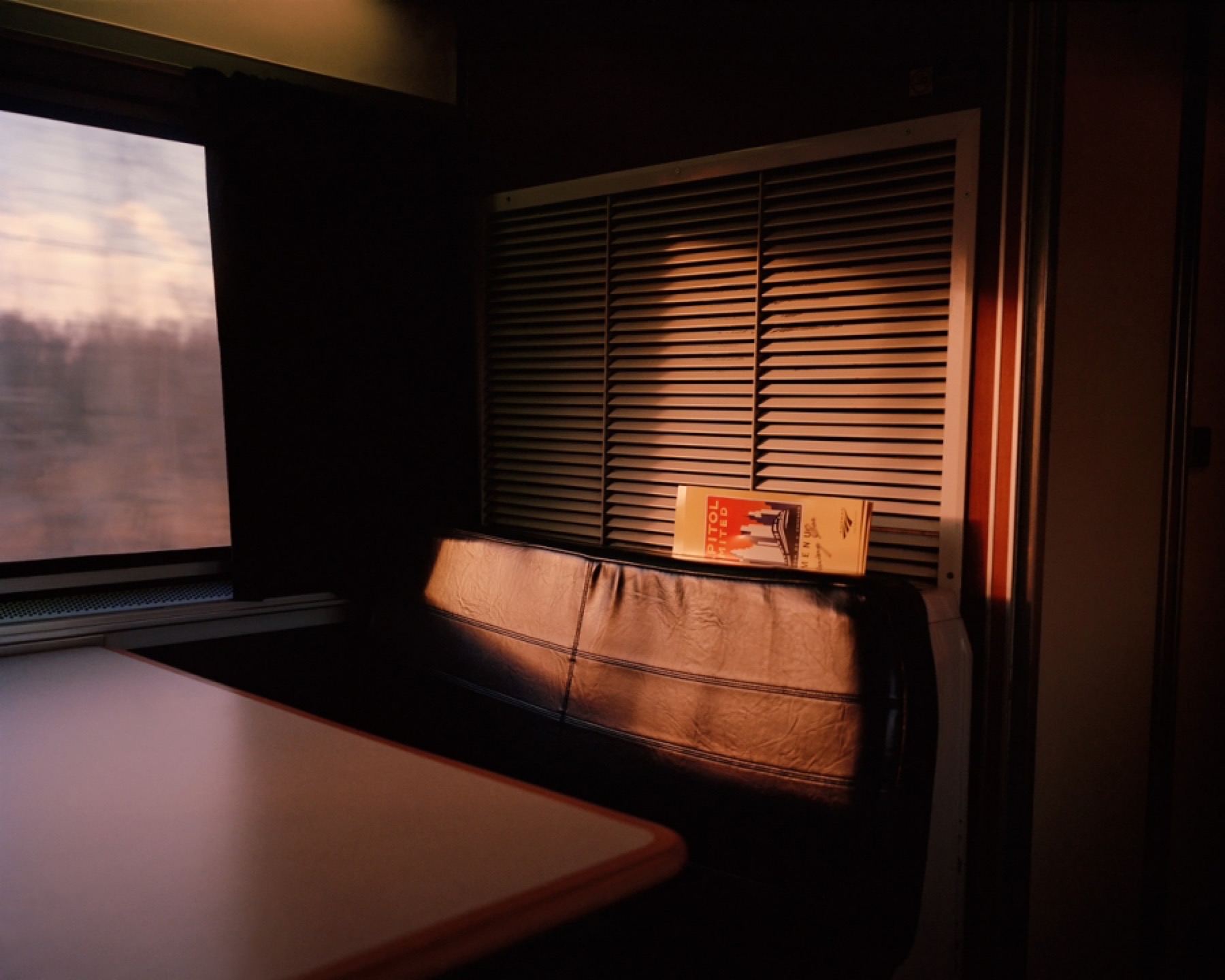

"Capitol Limited 12001," by McNair Evans. Courtesy of Sasha Wolf Gallery

Places that Have No Names

By Holly Haworth

El Paso to Lynchburg by Train

DESERT

I took the train out of El Paso on a Saturday afternoon in August. After a long stay in the Guadalupe Mountains of West Texas, I was going home to my Appalachians, the Blue Ridge of Virginia. I could tell you more about that summer—about loneliness, maybe—but this is not a story about that. I could tell you how I spent my days watching storms roll across the high desert in sheets of blue, how the Mexican hats were blooming, exuberant, and the red flowers of the spiny cholla unfolded like roses. And that, though I was lonely, there were the flowers and the storms, and long narrow canyons in which I could lose track of time, and I did not want to leave and go home. I could tell you a lot, but instead I’ll just say that I walked into the cool marble station and checked my bags at the ticket counter. I waited on one of the long wooden benches that was like a pew in an old church, where motes of dust were drifting in shafts of soft light while the Sunset Limited was readied for departure.

In late afternoon, I boarded. As the train began to roll, I felt the weight of it on the tracks, felt the tracks beneath us. As we pulled away from the station, El Paso from the window was desolate, monochrome desert. Hard brown earth. Red graffiti on silver boxcars glinting in the sharp sun in the rail yard. The train rolled out through El Paso, past the used car and auto-parts lots, handwritten signs in Spanish fastened to chain-link fences. It rolled out past that border city that looks down into Mexico. Rolled out into the desert. Cactus, rock, yucca. The emptiness, the color. I listened to the sound of scraping rails, flinty, like the cleaning of bone. The whine and high whistle as we passed towns and crossings, pulled into stations.

There are places that have no names, places that lie between one place and another, in-between places. Somewhere out there in the desert, between two stations, El Paso and Alpine, there was a wedding. Twenty or thirty people gathered under a patio with wooden beams holding a wooden roof over them. There were white streamers and a white gown, and many dresses and suits. There were cowboy hats and belt buckles and blue jeans and dust-brown skin. There was a glass punch bowl out there in the desert, fuchsia juice and slices of fruit, and there was a train sliding by as the guests filled their plastic cups from a silver ladle.

At Alpine, I stepped onto the platform just as the sky was turning pink. An elderly man hobbled down from the train and took a photograph of the stucco station with the camera that hung from his neck by a thin cord. I walked under clouds of cigarette smoke gathering above groups of folks talking. A man and a woman were swaying; they looked a little drunk. As I passed, the man flicked his lighter, small flame touching the tip of the woman’s cigarette. “I am happy,” she said to him through her cigarette-clenching lips.

Behind the station was an old white-brick factory building, BIG BEND WOOL & MOHAIR block-lettered onto the side in fading red. I wondered what it would be like to keep walking into that unknown town, to disappear from the place I had left and the place I was going back to, to fall into the place between.

People were boarding from the station. A young woman in a blue dress stood on the platform with her luggage. She had freckles, a long careful blond braid on the side. Her children clung to her and hugged her. Her husband kissed her, and she closed her eyes. Behind her, the pink sunset sky reflected in the train windows.

I returned to my seat. Four old women and a young girl of perhaps eight had boarded in Alpine while I was out walking the platform. The women were talking in Spanish. I listened to that warm, rolling language, catching words here and there. I imagined that the women were all my grandmothers. The girl was quiet in her seat across the aisle from me, her face pressed to the glass as the train started to roll. There may have been hot tears at my eyes, though I cannot exactly say why. Something shaken loose that I cannot precisely name.

Setting sun. The woman in the seat behind me stood up. She was short, looked to be in her seventies, with dark poofy hair, the kind you can see through, the kind that has a lot of space in it.

“Did you know we are going to go up a big hill?” she asked me in a deeply accented English. There was a hill in her mouth when she said it.

“No,” I said.

“Yes,” she said, “we are going up a big hill, then we are going to come down the other side.” Her eyes were lighted, and she was looking at me, smiling, as if together we would experience something magical. She nodded then moved on, toward the bathrooms at the end of the car, stumbling some. The train engine fired and we rolled out over the glowing land.

I watched the earth grow redder. Red rocks curving like animal bodies, like large reclining megafauna settling into soft, stony sleep on the floor of the desert. We would be in San Antonio by morning. But first we would climb a big hill and come down the other side.

NIGHT

I heard one of the women talking, muttering dreamily, ¿dónde estamos?, pulling back the curtains. Another station. The others roused, too, responding, all of their voices rising in conversation, words more rapid, velvety. Passengers boarded. Then we pushed off, the hum of the rails again, out and over the dark land, and they quieted, and we slept again.

The night went on this way, the women’s voices rising at each stop, rustle of curtains, peeking out at the small stations. I heard the names of places as I awakened. Altuda. Del Rio. Uvalde. Sabinal. Hondo. The women seemed to have the unflagging excitement of children. With the wakefulness of old nuns keeping a prayer vigil, they lulled between stations but never seemed to sink entirely into unconsciousness. I imagined the desert spooling out behind their eyelids, the rivers, the dry washes, the rocks, how that land was etched into their dreams, how it unfolded. Repeatedly I glanced back and saw the oldest of the women vaporizing and rematerializing. I do not mean her voice that I heard and then did not hear, but her body, what I beheld with my eyes—she was a vapor, mere smoke, then solid again.

SUNDAY

Finally, the pale of morning. San Antonio. The old women disembarked, huddled together, the girl swept along with them. I stepped out into the air. It was clear and starry, sky the faintest blue. I walked the platform, up and down. A large woman using a walker approached the door to the rear car, breathing heavily. She set the walker down, rattling it against the concrete, and stood looking up into the train, her heavy pocketbook hanging on her shoulder. I went over to ask if she needed help. “Bless your heart, oh bless you,” she said to me, folding her walker and setting it up into the train ahead of her.

The orange fire in the east spread across the sky, whitening the blue and burning away the dawn-twinkling stars. When the sky was bright with full morning the train began to let out hot exhalations, and I boarded.

As we left the city, I saw that I was in a different place than where I had begun the day before. There were round bales of hay in the fields. There were fields. I rolled the name of that place quietly over my tongue, that place that is somewhere between desert and swamp. San Antonio, named by Spaniards on a 1691 expedition for Anthony, the patron saint of lost things and lost people. By the train tracks, in patches of dry grass, there were sunflowers turning their round yellow faces to the east.

It is a Sunday morning in August, I thought, and I am on a train. The woman I had helped onto the car was sitting two rows back. Her body filled the seats. Her hair was pulled into a high ponytail. Another woman sat two rows behind her. She was older, thin, with short hair. We were the only ones in the car, our car the last in the row.

I was tired but could not sleep. The movement of the train was electricity in my skin. Steel wheels on hot steel tracks made a high harmonic sound. It was a faraway polyphonic current shot into my veins. The light was flickering through the windows across my face.

The women had introduced themselves, were talking about church. The large one, Sharita, said, “They call me Sister Hallelujah.” The other woman was Barbara. Sharita said, “What I do not want to be, Barbara, is a member of a mega church. I wanna know my pastor.”

“Amen,” said Barbara.

The women talked from their seats, each facing forward, as if they were shouting up to me.

“Barbara,” said Sharita, “a lot of churches done got so political they forgot why we was there—to give God all the praises.” She heaved her weight into the word praises.

“Ain’t that right,” said Barbara from the back row.

Sharita said, “There is no sweeter sound to God than your voice, Barbara.”

They raised their voices up, behind me, above the seats.

BEYOND THE TREES

All morning it was just the three of us in the car. The women talked about their lives. Where they came from, where they were going. Health problems, doctor’s appointments, husbands, children, grandchildren. Sharita is from Pascagoula, Mississippi. Barbara is from Buffalo, New York, but moved to Alabama thirty years ago. Sharita lived in New Orleans twenty-seven years. Her folks are from Camden, Alabama. Barbara was headed to her daughter’s wedding in New Orleans. Sharita’s husband died of a heart attack. There were no stations for hours, and the train picked up speed.

“Boy, we have got going fast,” said Barbara. It felt like the acceleration of a plane on the airstrip, before takeoff, at that fraction of a moment when the plane leaves the ground, wheels not quite picking up completely from the earth yet wings beginning to accept the push of the air against their metal bulk. One does not ever know the moment a train might slip or lift off its rails, I thought. The train slid wildly forward.

Sharita talked about her folks. “They have bright eyes, Barbara—their eyes have life in them. They are getting older, but life is still in their eyes. Ain’t that a blessing, now?”

I watched out the window, sun warm on my face. Beyond blurring lines of trees, straight-tilled rows in the marshy fields stretched to the distance. The fields went by with fleeting clarity, intermittent green beyond breaks in the trees. We were somewhere near a town called Sandy Fork. Sharita was talking about her husband.

“Shit, I miss him so much, Barbara,” she said. “If my husband were still alive we’d be married forty-four years. I was three months pregnant when I graduated high school. I had a scholarship, but I wanted to get married. I wasn’t old enough. My father and mother said, ‘Sharita, if you love him.’ They signed the papers and we got married in September. The night of the wedding, it seemed like the heavens opened up, it rained so hard. It was the first time I seen my daddy cry.”

White birds flashed in far field, then they were lost behind trees. I thought of the letter a friend had written that delivered bad news. But, my friend wrote, she had seen egrets on her way home from the doctor, hundreds of them—no, thousands. An outpouring, a blooming, a spring tide, a wayside congregation in the prison pasture, the prison she uses as a landmark when giving directions to her home in South Georgia, where the names of flat dirt roads are known but not posted on any sign. The egrets, she said, were white bandages on her wounds. Nurses in uniform. Feathers sweeping like prayer flags, love letters, emissaries.

Beyond the line of trees, I saw flocks of white birds in the soggy fields of late summer, standing on long thin legs that looked too thin, too delicate to hold them up. I watched them through the blurring trees, standing, then lifting and drifting.

SWAMP

The women had begun to yawn dramatically, like girls at a sleepover.

“I believe I’m gonna have to close it down,” said Barbara.

“Shit, I’m gonna close it down, too,” Sharita said. Between yawns, Sharita said, “Shit, Oh Jesus. Oh Jesus.”

Then the car was quiet. The train vibrated my body, its steady rhythm in my chest, in my belly, pulsing in the soles of my feet that were against the footrest of my reclining chair. I got up from my seat and climbed the narrow stairs at the front of the car that led to the upper level. I walked through coaches full of passengers who were deep into the lull of the train. Sprawled-out people, dozing, winking, unspooling, spilling into the aisles. Children on fathers’ and mothers’ curving laps and sinking shoulders, blankets covering round shapes that rose and sunk rhythmically beneath. Some reclined with eyes open, steady on me as I passed their seats.

I arrived at the observation car, where windows spanned the two walls from top to bottom and side to side, making the country a rolling panorama. And us inside a rolling diorama, to anyone watching from outside. As we neared Houston, the land was turning swampier and scrubby pinewoods began to pop up.

The train engine was a bass thrum in my head. Like a vision in my bones, I saw a history: the smelting and casting of the steel sections of track, the felling of the trees (oak, probably) and hewing of ties. The laying of the track onto ties, the pounding of spikes that fastened track to tie and tie and tie and tie, on and on across the land, rhythmic clanking and sharp clacks of mauls, the driving of spikes by what hands, and the songs that were sung by whose throats to that hard music of hammers. I heard it, high in the ears. I dozed.

Sometime later, I woke. A woman was coming up from the bar, mumbling aggressively. Her head jerked from side to side at the other passengers. Her eyes alit on a woman, and something flared behind them, crystal fires. You fucking bitch, what the fuck are you staring at? she yelled. She pointed at the woman, whose mouth was hanging open. Fuck you! she continued, moving closer, pointing. The instigator’s male companion, following behind, daintily touched her arm. You fucking crazy bitch! she yelled. She pointed her finger at her target, whose mouth remained agape.

There were whispers like soft waves moving up and down the observation car, heads turning. I put my head down, stared harder into the book that I had compulsively opened, a place to fix my vision. I bored my eyes into the page of mashed-together symbols, kept the woman in my peripheral. Finally, suddenly, she staggered away, slammed her hand against the flat button that opens the sliding door between cars, and her companion followed. There were little ripples of relief throughout the car, afternoon sun bright on us, and everything felt calm, light even.

SOLID EARTH

“Man is going to Mars and Jupiter, shit, Barbara, cloning and all that shit. I mean shit,” said Sharita. The announcer came over the loudspeaker. Houston, Texas, ladies and gentlemen. Sharita continued: “You’ve seen it up there in space. They can just stay up there, I can’t do it. They’re destroying this world. Man is rushing God, trying to make Him come back.” Ladies and gentlemen, once again, Houston, Texas, the speaker crackled.

I went out into the hot stifled air. Angular buildings towered into the sky, windows reflecting the blue and multiplying it. I smelled the bayous, and asphalt. The train belched, sitting there like a heaving, exhausted beast. Then it was time to go.

In the afternoon we slid into Louisiana, past the chemical refineries of Lake Charles and Lafayette, the gas flares, and at sunset we halted and braked into Schriever. I watched as the sun slipped down into the flatland and lit it, and young children—friends, cousins, brothers and sisters, maybe—rode their bicycles alongside the weedy tracks, bare feet pedaling forward while heads gawked sideways through the windows of the train. Wondering, maybe, where the faces of the strangers inside had come from, and how far each of us would go, how far the country stretched out to other places. Night fell.

In New Orleans, looking out at the dark city, I felt the tug of the Mississippi on down into the Atlantic, felt the drain and suckage. I gathered my bags and walked into the station, where I would sleep for the night. Once on solid earth, away from the whirring harmonic rails and the pluralistic whistle of the train, my ears began to ring. My body felt watery, my head light. I stood in one place, but I was still hurtling forward, down the rails. I was doubled over in the bathroom that night, as if my body could not accept the stillness or the silence of the station. Waves of nausea wracked and wracked me. Then I heard that the station was not silent after all, that there was jazz coming out of the speakers on the ceiling. Jazz. The cool tiles felt good against my face.

BOTTOMLESS LAKE

In the morning, we rolled out on the Crescent, past cemeteries with rows of mausoleums, leaving that city I have visited many times and in which I have never not vomited. I thought of all the skeletons, of bones and skulls, sitting neatly or askew (who would know?) inside wooden caskets that were inside stone boxes, light seeping in through the cracks. I thought of the train cars like the beads of a rosary, a recitation whispered as each car slipped past.

Two days before, on my way to the El Paso station from the Guadalupe Mountains, through the Chihuahuan Desert, I was riding in a car with a woman I had met in Texas, a friend of a friend, a woman who is a rancher and plays fiddle in an old-time band. Her two blond-haired children—Emmett, four, and Rhiannon, seven—were in the back. I had told them that I would be taking the train to Lynchburg, Virginia. Their mother and I had listened to them conceiving of the distance and the journey. They talked of one day taking the train and where they might go. Rhiannon did most of the planning, and Emmett quietly turned things over, looking out the windshield.

As we came to the outskirts of El Paso the children asked their mother to hear a song called “The Bottomless Lake.” The one by John Prine, about a family who sets out on a trip, and their car falls into a bottomless lake. (Bad brakes.) Rhiannon prided herself on being able to sing the entire song; she chimed in at the middle of each line, so that her words became a bright and hurried echo of Prine’s, she at his heels, stumbling to catch up. The family in the song sunk down and down into the bottomless lake as I prepared for my own long journey. At the chorus Rhiannon sang, loud—I’m so scared I can hardly breathe, I may never see my sweetheart again, and I wiped away tears from behind my sunglasses.

There was a man in Virginia, see.

I might have loved him and he might have loved me had things been somehow different. But they weren’t different. They were how they were, and the trip had loomed ahead of me with that fact waiting at the end of the line.

Now, leaving New Orleans, coasting over Lake Pontchartrain, I thought of sinking and sinking into the bottomless lake, sinking forever, as the beams of the bridge whirred past and I watched that shallow lake, whose name has a train inside it, stretching out and out. Birds glided over it, alongside the train, unaware of human heartache or the heartache of slow, moaning trains crossing wide miles of water glinting endlessly in each day’s morning sun.

BREAKFAST CAR

After what seemed many hours, we were over land again. I was hungry, and I took bread and peanut butter from my bag and walked up to a car adjacent to the one in which breakfast was being served on white tablecloths. I sat at a card-playing table in the empty car for my hobo breakfast. Through the small window in the connecting door between each car, I saw the yelling woman staggering down the aisle. She was walking toward the front of the train. It seemed she had her faraway eye on the dining car. Her companion was not following.

Since last night she had changed into a pink ankle-length velveteen nightgown with white lace at the collar. Her form grew larger, more clear, as she neared. The gown became pinker, brighter. Underneath it I could see that she wore no bra. As she walked, her large breasts swung and bounced behind pink velveteen. She did not walk. She sauntered. She lumbered.

I chewed. I closed my eyes against the sun. I knew she would be there when I opened them. I knew she would be sitting across from me, that she was looking through my eyelids already. I swallowed, breathed. Opened my eyes. Though I had expected her, the sight of her face sent a jolt that ran the course of my body. I felt little needle-pricks in my cranium. Her dark ringlets were wet, hanging down.

Good morning, she said. You want breakfast? She spoke in the muffled tones of whales, but I heard her. She had asked me if I wanted breakfast, though it was I who was eating breakfast and she who was not. Can I have some bread? she asked. She had already pulled the bag toward her, but she waited for my answer. For a moment we were suspended that way, her eyes hungry.

“Of course,” I said, and she stuffed her hand into the bag, pulled out the top piece and tore it with her teeth. She chewed open-mouthed, smiling at me. I smiled back. She was pretty, I thought, even while I was repulsed.

Thanks, cheers, she said through her bread. She raised the remainder of the slice up into the air in triumph, held her bread-holding fist aloft, and I was triumphant, too, though I cannot say why. She stood and floated away. By then we had slid past Slidell and into Mississippi.

BEGINNING

The day went on. It went on and on. The incessant rumble of the tracks waxed rhapsodic in my kneecaps, my collarbone, my sternum. The fluid, continuous ringing of steel on steel was like one of those Tibetan singing bowls, a sound that opened space in my eye sockets.

We went through tall pines, sunlight flashing. Sandy lawns in front of little houses. I was not on the way somewhere, but only just where I was, in a moving chair, while some unseen conductor was conducting. In the observation car I lay across the seats and felt very small.

Picayune, Hattiesburg, Laurel, Meridian. I said the names of those places, walked the platforms of the stations, up and down.

From the window, the land looked wet, a sponge that could not soak up all the water. Red trumpet creeper, its flowers like tiny tropical birds. Lily pads on a pond like revelations. The day rolled away. Toomsuba, Tuscaloosa, Birmingham. From the rear of the train I could see through the window the first car as it curved far ahead into the trees. There in Central Alabama sit the southernmost undulations of the Appalachians—the beginning, or the end, of them, depending on which direction you are going.

Here, they were beginning. I saw that the Joe-Pye weed had just started to bloom.

Chugging hard into Georgia, I felt we were crossing a threshold. Everyone slept through pine farms and basketball goals mounted to telephone poles, nets long rotted away, and the Southern Gentleman Lounge, and the smoke of hickory pluming from little red shacks with BBQ painted on the side.

I passed the yelling woman where she lay sprawled on the seat, now in a white nightgown, head drooping on the shoulder of her companion, eyes sedated-looking. But she saw me. Her face flickered with recognition. She pointed, sat up. She’s sleepwalking! she yelled in accusation. I had been revealed, stripped down. You’ve got to wake up!

I kept going. Up and down, I walked, pausing for a moment—a second or two—in the space between cars that smelled like heat and grease, where the hot air whooshed in, that space that is both inside and outside the train. I looked down through the crevice between the sliding cars to see the earth: tracks, rocks, and dirt, so close, blurring by beneath us. Each crossing was a moment when one had to trust the step that is between one place and another, that shaky place between places.

It went on that way. I would be home by morning.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.