Pink limo at Graceland Too | All photos by Christopher Blank

THE FINAL DAYS OF GRACELAND TOO

By Mary Miller

I never met Paul MacLeod, never took a drunken middle-of-the-night trip to Graceland Too, and this was my last chance to see it. The contents of MacLeod’s home-turned-Elvis-museum would be auctioned off the following day.

A friend and “lifetime member” drove me the thirty minutes from Oxford to Holly Springs, Mississippi on a Friday afternoon, the day before the auction.

“How many times did you have to go to be a lifetime member?” I asked.

He couldn’t remember. Perhaps it was only once, maybe twice. He had no token to prove his membership but he enjoyed saying it—“lifetime member,” he repeated. I adjusted my seat in his boat of a Lincoln Town Car, the same car my father used to drive. This friend was in love with me or perhaps he wasn’t in love with me but he frequently invited me over to his house and cooked quail and steak and various other meats that I hadn’t told him I didn’t like. The quail, in particular, had been a mistake. So many bones.

I’d always pictured MacLeod’s house on a desolate road, isolated from the rest of Holly Springs, but it sat on a corner in a normal-looking neighborhood. A pink limo was parked out front, stuck-on letters advertising GRACELANDTOO 1853 and USA. On each of the back windows: VIP. The house looked large from the outside, but inside the rooms were cramped and the ceilings low and it was obvious that nothing had been repaired in decades. The upstairs was cordoned off with chicken wire. I wandered the rooms taking pictures with my cell phone while my friend talked to someone who claimed to be MacLeod’s lawyer. He said he’d made t-shirts and gestured toward the mannequins, which were horrible and diseased-looking with missing appendages. The man was pantless in a baby blue “Graceland Too Forever” t-shirt while the dark-haired woman wore pink.

Hipsters with nice cameras roamed about. One of them interviewed the auctioneer in what might have once been a dining room. The auctioneer was extraordinarily tall, in a camouflage jacket and cowboy hat, his head nearly touching the ceiling. Both of his thumbs hooked into the pockets of his jeans.

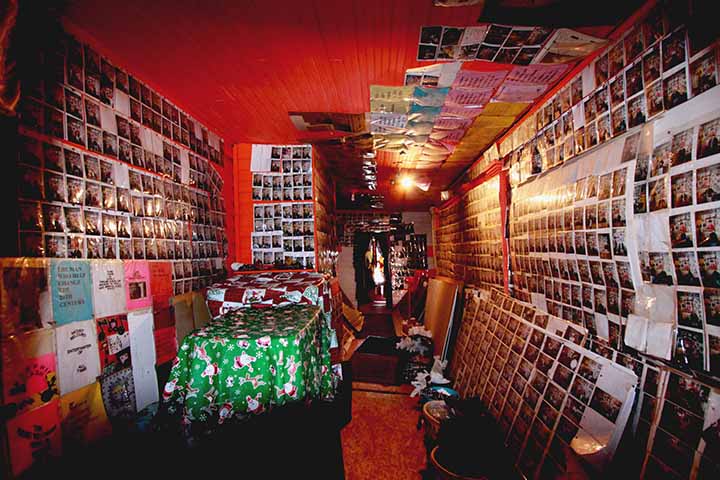

Inside Graceland Too | Photo by Christopher Blank

Inside Graceland Too | Photo by Christopher Blank

MacLeod took a photograph of every visitor to his home, and there were thousands upon thousands of images tacked to the walls, some of which were strung up outside on a clothesline for viewing. My friend looked for himself while I looked for familiar faces, hoping to recognize someone—to pull a picture out of its slot and pocket it. There were so many faces, so many it was hard to believe that I didn’t know a single one of them. Otherwise, there was nothing I wanted: not cracked busts of Elvis, pink toy limos, posters, ancient computers, jumpsuits that Elvis may or may not have ever touched, pictures of The King shaking hands with Richard Nixon and other famous people (I liked the idea that famous people also wanted to take pictures with famous people). There was a jumble of Christmas decorations in one corner—a couple of Frostys surrounded by Mary and kneeling Wise Men—and hundreds of videotapes and old TVs stacked one atop the other like a department store display.

Did MacLeod play Elvis videos on all of the TVs at the same time? What would it have been like to actually live here, to inhabit a place so cluttered that the town considered it a fire hazard? I imagined the house in flames, imagined those flames jumping from one house to another until everything had to be demolished in order to contain the blaze. The whole town destroyed.

On the lawn, dozens of trunks like the kind I used to take to camp at Strong River formed neat rows. I missed those trunks, cheap and boxy, and how my mother had written my name inside my clothes, even my socks. I recalled the weeks I’d spent at camp: mosquito bites (“slap don’t scratch”); eating watermelon while standing ankle-deep in water; the way I’d play sick or injure myself in order to leave early, though my parents always insisted I stick it out. And every year, inexplicably, I agreed to go back.

I stood on the porch and watched the people.

“MacLeod died in this chair,” an old man said, giving the arm a few pats. He smiled up at me as he rocked. “If you buy it, you get me, too.”

“That’s quite a bargain,” I said. “Quite the deal.” He laughed. He had probably said the same thing to every woman who’d walked by. I had my friend take a picture of me posed in front of one of the lions guarding the house.

Later, I looked it up and it was true—MacLeod really had died in that chair.

He had dedicated his life to Elvis, to the remembrance of his hero. It was said he never forgot a face and drank at least twenty-four cans of Coke a day. His death from a heart attack two days after killing a man who’d tried to break into his home was a tragedy befitting The King. And although he’d conducted tours of his home twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, three-hundred-and-sixty-five days a year, I’d arrived too late.

“Look,” my friend said. “TLC MARY TCB.”

“That’s me. Taking care of the business,” I said, and I snapped a picture of the wooden letters drilled into the porch, a bit of my finger blurring the edge and the perfectly blue January sky.

Elvis Shrine inside Graceland Too | Photo by Christopher Blank

Elvis Shrine inside Graceland Too | Photo by Christopher Blank

Read “Like a One-Eyed Cat,” by Randal O’Wain from our Summer 2015 issue.