Editor’s Letter: Big Brother

By Danielle Amir Jackson

"The Improvised Flowers," 2021, mixed media on canvas by Guglielmo Castelli. Courtesy the artist and Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo, Brussels, New York. Photograph by Nicola Morittu

Ed came home on his twenty-first birthday. It was five days before my fifth; soon I’d be able to start real school! Mama and I baked a pound cake. Ed lived in the dorms at Memphis State, where he was a full-time student in engineering. For tuition and spending money he waited tables and tended bar on Mud Island. My brother was creative, funny, and very knowledgeable about music—especially jazz. His grades were not the greatest in high school. But he tested off the charts, and he could write and draw and draft and reason. He figured out engineering wasn’t for him through trial and error. By the time college was over, he’d changed majors and focused his talents enough to make regular appearances on the dean’s list.

It’s easier to take risks, to try, and fail, and try again when you have access to models of fortitude, audacity, or courage. For this issue, OA contributor Jodie Bass asked the multi-dimensional visual artist Sanford Biggers many delightful and probing questions, including this one: Where does your courage come from?

Biggers’s reply stuck with me:

I think maybe being the youngest kid. My brother and sister are eight or nine years older than me and are really intelligent—academics, doctors, scientists, all that stuff. And as a kid, I had to sit at the table and listen to those conversations when I could barely pronounce the words and then find a voice—to speak with them and have an opinion.

The answer was disarming and intimate—about a private family life and the practice of love among siblings. And the challenges and tensions which reside there but provide fruitful fodder for our lives. It reminded me of Tarisai Ngangura’s essay on Carolyn Franklin, Aretha’s baby sister, in last year’s music issue. “Carolyn is remembered because her sister is worshiped,” Ngangura writes. “That’s the thing about siblings in Black music-making. We see them all, even when only looking at one.” Both quotations resonated because of my own life, in which two much-older siblings accomplished many feats and made for me a lighter load. They accumulated knowledge and information, many times through slights and disappointments. Resilience, we often forget, is conjured through peril. They are the ones I would follow off Hubert Circle, out of North Memphis, onto the MATA bus, across town to the Main Library and the school out east and onto the plane, ultimately, that took me to undergraduate school in D.C.

Being the youngest by so much meant being born into a world already created, and then, vacated as they’d aged into new pursuits. I remember the residue of their childhoods: the yellowed sheet music, from “Ben” and “To Sir with Love,” still stored in the piano bench. Drawing pads full of old superhero sketches and detailed renderings of buildings and city blocks; trumpet mouthpieces, alto saxophone reeds. I would join the band, too, Mama said, influenced by how much my siblings had learned playing instruments. Kim pursued engineering, following our big brother, and stuck with it long after he’d moved on to graduate school in public policy. A few years behind Ed, she followed him often; in many ways, we still do.

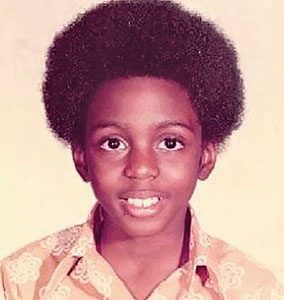

Childhood photo of Ed Bryant, the author's brother.

Big brothers are born leaders, parents’ helpers (often by accident or out of necessity). They’re almost always the kind of people I’d call “naturals”—they don’t have to overcompensate and work to be liked the way little sisters learn to do. How annoying! And also, how useful. I know what kind of energy to channel when faced with challenges that benefit from a cool self-assurance. I have a model in mind.

For this issue, the second in our thirtieth-anniversary year, our writers show their fascination with models like these: role models, pioneers, antecedents, ancestors, mentors, artistic kin, chosen family, uncles, big brothers, and fathers. After several back-to-back issues that hewed to a particular theme, we began work on this issue hoping to explore whatever was most pressing on our contributors’ minds and hearts. As is often the case with creative people in a particular moment, our writers shared many preoccupations. Something about our present-day circumstances—raging wars, book bans, gay bans, homelessness bans, all amidst the third year of a global pandemic—has caused us to think about guidance. We are seeking it out, wondering about its nature, dreaming about answers and action and compassion. Many of our writers were particularly concerned with male guidance, male figures, and masculinity, broadly defined—yours and mine. What, they wonder, makes a man? Who has access to manhood? Can masculinity be wielded softly, with tenderness, in ways that benefit us all?

This edition’s Points South is all about men, and our writers envision masculinity in bold new ways. Longtime OA contributor James Seay wonders about manliness and ableism, while first-time contributor Kaylie Saidin renders, in fiction, a portrait of an old-fashioned patriarch who seemingly defies redemption. Tauheed Rahim II has a “big cousin” who serves as “the family griot,” reminding Rahim of his connection to a powerful ancestral line. Jeremy Redmon remembers his father, a decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, with love and sensitivity. The writer is demonstrative with his own son in ways that his father, sometimes “taciturn, withdrawn,” could not be. And KB Brookins finds in the music of Frank Ocean a model for loving and living without constriction.

I’m proud of this collection of features, where you’ll find Stephen Kearse’s reporting on a civil rights “cold case” from 1960. Mattie Green, a mother of six, died one morning in mid-May after a bomb exploded during the night beneath the home she shared with her sleeping family. Saeed Jones debuts stunning new work from his forthcoming book of poetry, Alive at the End of the World. And from our archive, a story on Carson McCullers, written by Elizabeth McCracken in 1996, is introduced with a new essay by Jenn Shapland, whose search for literary lineage is its own model of respect and careful inquiry.

Also searching in their own way are Jodie Bass’s interview with Sanford Biggers and Irene Vázquez’s essay on an art installation at a gallery in Chelsea. Part of the section of the magazine we dedicate to arts writing, both pieces seek connection with ancestors and tradition while looking outward, engaging new ideas and new people, and by looking ahead.

We want to make the magazine you want to read. Let us know what stories feel urgent to you by emailing us at feedback@ oxfordamerican.org.